Browse our collection of crime reviews and ratings.Showing 12 of 20 reviews.

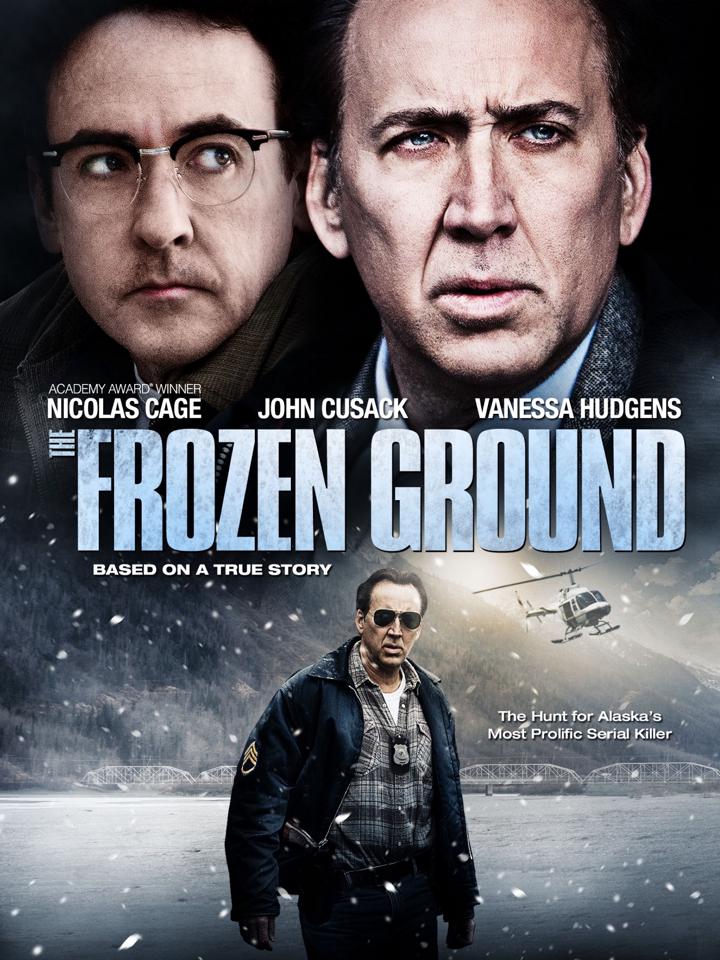

I went into The Frozen Ground not expecting much, but it was a surprisingly gripping crime thriller based on true events—specifically the hunt for Alaskan serial killer Robert Hansen. The story follows a state trooper, played by Nicolas Cage, as he tries to bring the murderer to justice, with some help from a survivor (Vanessa Hudgens). What really grabbed me was the icy, isolated setting—it creates this haunting atmosphere that makes you feel the danger lurking in every snowy corner of Anchorage. Nicolas Cage delivers a pretty restrained and emotionally believable performance, which, frankly, I wasn’t expecting. He brings a sense of weary determination to his role without going over the top. John Cusack, as the seemingly unremarkable but sinister killer, is actually chillingly effective. The casting works in the film’s favor because both leads are a little out of their usual wheelhouse, so it never feels formulaic. This isn’t a “flashy” crime thriller; the pacing is deliberate and stays focused on the investigation rather than big action set pieces or wild plot twists. That might be a downside for some, as certain stretches can feel a bit repetitive, but I appreciated the way it leans into the grim realism of police work. There’s a palpable sense of frustration and desperation that grounds the story. Visually, the movie does a great job capturing the bleakness and cold. The use of natural light, snowy streets, and remote cabins give every scene a stark authenticity. Some of the dialogue, though, can be heavy-handed at times—especially side characters who feel more like exposition machines than real people. It’s not flawless, but the overall mood and tension make up for occasional clumsy moments. You would enjoy this if you like crime stories based on real cases and don’t mind a slower build or bleak subject matter. It’s a solid watch for fans of atmospheric investigations and performances that try something a bit different for the actors involved.

Gomorrah is an Italian crime drama that takes you deep into the gritty world of the Neapolitan mafia, known as the Camorra. It doesn’t glamorize organized crime—instead, it shows the difficult, brutal realities of life in that world. The story follows Ciro Di Marzio and the Savastano family as power struggles, betrayal, and shifting allegiances unfold across Naples. There’s a cold, unrelenting realism here that sets it apart from flashier American crime series. One thing that really stands out is the way the show looks and feels. The cinematography captures the bleak, urban sprawl of Naples in a way that’s both beautiful and intimidating. The camera often lingers on rundown apartment blocks, tight corridors, and harsh streetlights, giving you a real sense of place. The soundtrack is minimal and moody, underscoring the constant tension in these characters’ lives. Gomorrah’s storytelling is relentless; don’t expect clear-cut heroes or “good guys” in this world. The characters are all deeply flawed and often make choices that feel both inevitable and shocking. The writing manages to balance moments of tense action with quieter, more introspective scenes, really letting you get under the skin of ambitious Ciro, cold-blooded Genny, and the formidable matriarch, Donna Imma. If there’s one thing that doesn’t always land, it’s the pacing. Some stretches, especially in the middle seasons, can feel a bit slow or repetitive, as the characters continue their cycle of revenge and double-crossing. Sometimes it feels like the show is almost too bleak, rarely offering a glimmer of hope. But the performances—especially Marco D’Amore and Salvatore Esposito—anchor it with a raw, believable edge. You would enjoy this if you like crime stories that are more grime than gloss, and shows that dig into the psychological toll of life on the wrong side of the law. If you want something different from your usual American or British crime fare, and don’t mind reading subtitles, Gomorrah is a gripping, immersive ride.

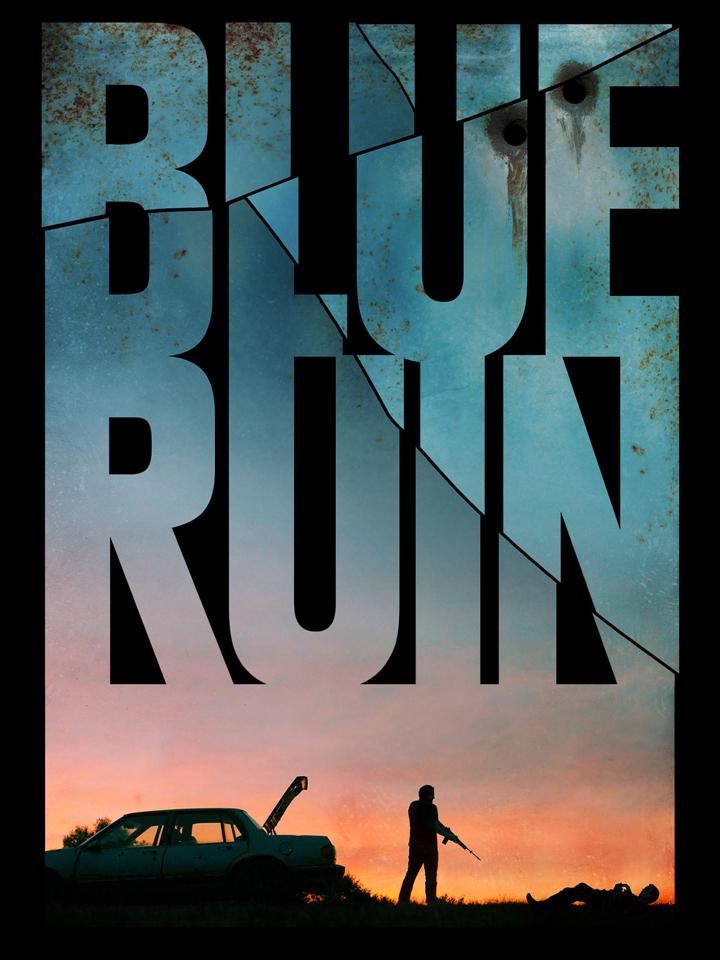

Blue Ruin is one of those quietly unsettling crime dramas that sneaks up on you. It tells the story of Dwight, a vagrant whose life is upended when he learns the man responsible for a family tragedy is being released from prison. There’s a simple revenge setup, but what unfolds is far less stylized than most revenge films — it's raw, awkward, and extremely human. What I love most is just how grounded everything feels. The protagonist isn’t some hardened action hero; he’s absolutely in over his head and it shows in every painful mistake he makes. There’s a constant sense of tension, and the suspense comes not from plot twists, but from the genuine unpredictability of Dwight’s choices. The violence, when it happens, is quick and messy, avoiding any hint of glamorization. Visually, the movie really makes use of its locations — desolate highways, rundown houses, and bleak motels. The cinematography strikes a balance between beautiful and grim, enhancing the film’s off-kilter tone. There's a feeling of small-town America that makes the whole ordeal oddly intimate, almost claustrophobic at times. Macon Blair, who plays Dwight, delivers a performance that is part haunted, part vulnerable, and it’s genuinely affecting. The supporting cast doesn’t get that much screen time, but every character feels solid, like you could walk past them on the street. The story is deliberately paced, which might not click with everyone, especially if you’re after nonstop action. You would enjoy this if you like your crime stories grim and realistic, with a strong sense of place and a main character who doesn’t always know what he’s doing. If you’ve ever liked films like Blood Simple or loved the more lo-fi Coen Brothers movies, Blue Ruin is absolutely worth a watch.

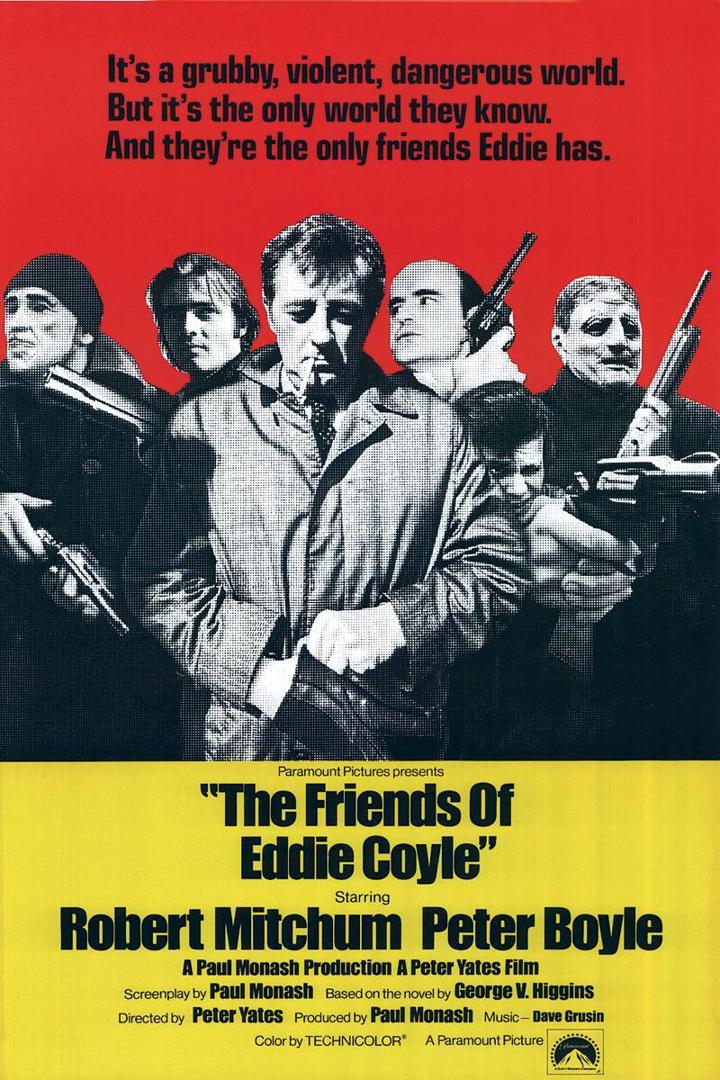

I finally sat down to rewatch The Friends of Eddie Coyle, which I always think of as the crime film for people who are sick of crime films. Even though it was released in 1973, about a decade outside the window you asked for, it really embodies what cops and robbers stories tried to become in the last forty years — slow-burn, anxious, and world-weary. (If that’s a dealbreaker, feel free to throw something at me, but I promise it holds up and keeps cropping up as a reference-point for modern crime flicks.) At barely 100 minutes, it’s an unflashy Boston underworld shuffle, more about resignation than excitement. Robert Mitchum plays Coyle, a weary small-timer with heavy jowls and heavier problems. The first thing you’ll notice is its sense of place. Every parking lot, factory breakroom, and fading Irish bar feels soaked in the kind of authentic, blue-collar malaise that makes you want to reach for both a cold beer and an escape route. There’s nothing showy about how Peter Yates shoots Boston—he just lets the peeling paint and traffic noise speak for themselves. This is miles away from the glamorous grit you get in later Scorsese or the locked-tight compositions of someone like Michael Mann. Here, you feel like you’ve truly wandered into these characters’ stomping grounds, whether you’re ready for them or not. Mitchum’s performance is what really holds the movie together. He gives Coyle a defeated, almost dog-like quality without making him pathetic. It’s the small stuff: his tired posture, the way he shrugs his coat a little higher against the cold, or the half-sincere chuckle he gives when someone asks about his “friends.” You’re never rooting for him in the classic anti-hero sense — he’s not clever enough for that — but you do want to see how long he can keep treading water before he finally gets pulled under. This isn’t a film that worries about big action set pieces. The two armored car robberies that happen around the story are as tense as you’d expect, but they’re shot with clinical detachment. There’s no pumped-up music telling you how to feel, no slow-motion heroics. The movie gets its tension from the spaces between the crimes — the uneasy deals brokered in donut shops, the wordless glances across bar tables, and all the men with tired eyes figuring out how to survive until next week without betraying the wrong guy. If there’s a complaint to be made, it’s that the film is almost too low-key for its own good. There are stretches where not much happens, just small talk and silent worry, and if you aren’t already in the mood for slow-boiled suspense, it will probably test your patience. Some of the supporting actors, too, are more functional than memorable. Richard Jordan’s cop is a bit bland, even if that fits the script’s sense of procedural exhaustion. But the minimalism does pay off emotionally. There’s a grinding inevitability to the way Eddie’s choices box him in, and it all lands without melodrama. The story doesn’t pity him or anyone else stuck in this grimy ecosystem. It’s honest: sometimes, no matter which side of the law you’re on, the house always wins. You can see the tiny betrayals coming way ahead, but watching how they play out — as undramatic as a handshake — is where the sticky sadness sits. Peter Yates really delivers by refusing to make any of these crooks seem cool or tragic. The supporting cast, especially Steven Keats as the tense gun-runner Jackie Brown (way before Tarantino borrowed the name), are all perfectly short on charisma. Everyone is lonely, scrabbling, and haunted by the feeling that their best shot was years ago. The whole film smells like spilled beer and old newspapers, and I mean that as a compliment. I wish I could say The Friends of Eddie Coyle set the world on fire when it came out, but it’s mostly become a touchstone for people who want their crime stories to feel lived-in, bitter, and honest. Its influence is everywhere, from The Town and Mystic River to the more dour seasons of The Wire. I’ve grown to really admire its smallness — the way it makes big questions feel like tired sighs, not shouts. It’s not perfect, but it’s lived-in as hell.

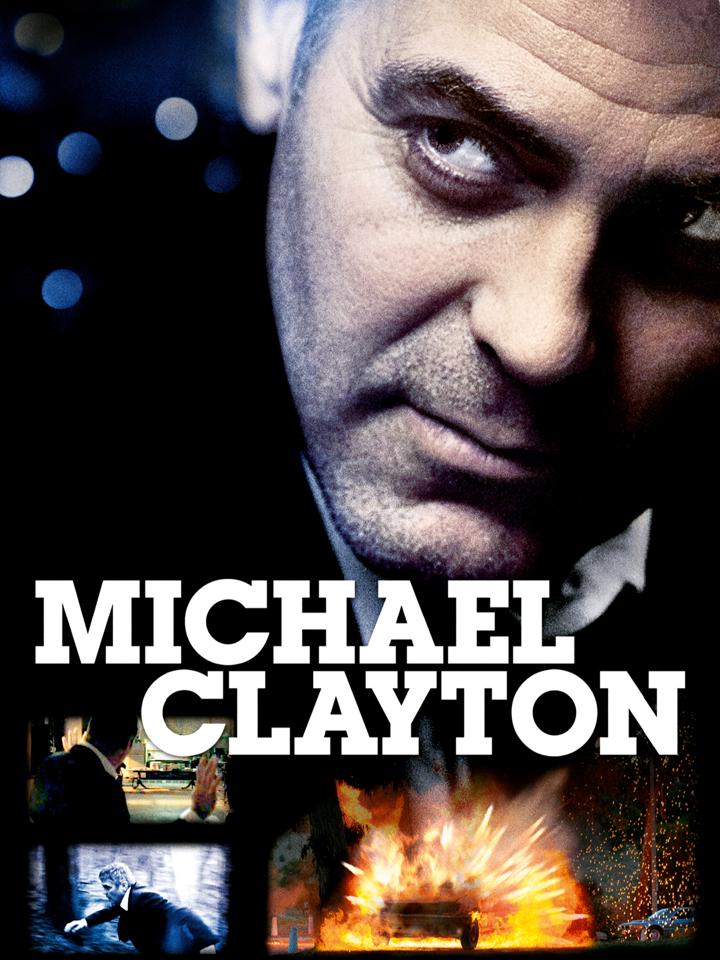

Let’s talk about Michael Clayton for a second. It’s one of those crime dramas that somehow feels both classic and modern at the same time. Released in 2007, this is Tony Gilroy’s directorial debut, starring George Clooney in what might be his least “George Clooney” performance. You won’t find big car chases or high-speed shoot-outs here. Instead, it’s a tightly wound story about legal dirty work, corporate cover-ups, and the quiet desperation that comes with knowing too much for your own good. The movie opens with a sense of unease and keeps the tension simmering beneath the surface for almost the entire runtime. Clooney plays the title character, a “fixer” for a high-powered law firm, the guy who gets called when things have already gotten messy. The plot kicks into gear when one of the firm’s top litigators, Arthur Edens (the criminally underrated Tom Wilkinson), has a very public meltdown during a billion-dollar lawsuit. The firm needs Clayton to contain the damage, but the more he digs, the more he’s forced to question the morality of his work and the people paying his bills. What really stands out about Michael Clayton is its tone—this film is cold, clinical, and almost suffocatingly tense, without resorting to melodrama. The cinematography leans into a kind of urban chill, with harsh fluorescent lights and sterile boardrooms. It’s the kind of visual style that makes you feel like you’re sitting in on a very bad day at work, and it works. It’s not flashy, but it’s deliberate. Everything feels intentional, from the muted color palette to the long static shots that let uncomfortable moments breathe. Clooney’s performance is proof that he’s more than just a Hollywood smile. He’s vulnerable here, beaten down but still sharp. There’s a scene in which he stands alone in a field with a trio of horses, and the look on his face—just tired, bewildered, one coat away from giving up—tells you everything about where he’s at emotionally. You also get Tilda Swinton in a role that is both icy and nervous. She’s perfect as the corporate lawyer scrambling to control what can’t be controlled. Pacing-wise, some might call it slow, and honestly, that’s fair. The movie doesn’t hand-hold. There’s a lot of quiet character work and a focus on process. The tension builds gradually, with moments of suspense so subtle you almost miss them. At times that patience pays off beautifully, but there’s a stretch in the middle where it risks losing the less invested audience. If you like your crime movies with bang and flash, you might zone out for a minute or two. What gives Michael Clayton real emotional weight is the way it focuses on the cost of compromise. Nobody’s clean here. You root for Clayton even as you watch him try to justify the unjustifiable. There’s a sick feeling to some of the choices being made, and the film challenges you to empathize with all the characters while never letting them off the hook. The writing is razor-sharp. Dialogue is realistic, almost mundane at times, but with a slow-burn intelligence that rewards you for paying attention. If the film stumbles anywhere, it’s that its emotional coldness can sometimes keep you at arm’s length. It spends so much effort on mood and atmosphere that when the big moments finally arrive, they don’t always land as hard as you want. The plot, for all its knots and reversals, is actually pretty simple at heart: company does bad thing, people scramble to cover it up, conscience fights back. The craftsmanship is so high, though, that it almost doesn’t matter. All things considered, Michael Clayton is one of the smartest and most adult crime movies of its era. It’s got no patience for clichés or easy answers. If you’re in the mood for something sharp, icy, and a little morally ambiguous, this will absolutely hit the spot. But fair warning, it asks you to lean in and meet it halfway, and if you’re not in the right headspace, it might leave you out in the cold.

Let’s talk about “Out of Sight,” Steven Soderbergh’s criminally underrated 1998 crime caper. This movie is wild because it’s so stylish and cool, yet basically nobody ever puts it at the top of their heist-movie list. If you slept on it, well, you’re in for a treat. Clooney, before ER completely typecast him, plays a bank robber whose quick-witted exchanges with Jennifer Lopez (yes, J. Lo, and yes, she’s really good) make the whole thing sizzle. The plot kicks off when Clooney’s character, Jack Foley, breaks out of jail and ends up literally entangled with J. Lo’s U.S. Marshal. That locked-in-the-trunk scene? Legendary flirtation. What really jumps out is the tone. Soderbergh manages to make everything feel light and steamy, but not flimsy. You get the sense that danger is always around the corner, yet there’s this breezy attitude with every scene. It feels like Miami heat and Detroit grit, sometimes in the same shot. The movie doesn’t rush—honestly, it might even take its time a bit too much in places—but since the dialogue is clever and the chemistry is off-the-charts, you get a little drunk on the vibe. Clooney is magnetic in his pre-superstar, post-teen heartthrob phase. He brings the exact right amount of roguish charm, so even when you know he’s kind of a loser—at least compared to more successful crooks—you root for him. Jennifer Lopez, meanwhile, is the real shocker here. She’s sharp, no-nonsense, and nails the mix of competence and vulnerability. You get why she’s intrigued by Foley, but you also believe she could snap the cuffs on him any second. Their cat-and-mouse energy makes the movie so much fun. The secondary cast is stacked. Ving Rhames, Steve Zahn, Don Cheadle, and even a brief Albert Brooks appearance. Everyone gets just enough to do, and nobody mugs for the camera. Steve Zahn, in particular, brings this anxious goofiness as Foley’s accomplice that never tips over into parody. Even when the script leans on familiar beats—a big score, double crosses, crooks getting in over their head—it feels fresh because the characters don’t behave in cookie-cutter ways. Soderbergh’s direction is peak 90s cool, without the Try-Hard Tarantino vibe that was so rampant back then. He uses jump cuts and flashbacks, but not in a way that screams “look at me, I can do nonlinear.” The color palette is memorable, with the warm Miami pastels clashing against colder Detroit grays, which telegraphs the shifting tone better than any line of dialogue. Elliot Davis’s cinematography deserves as much credit as the editing. That whole hotel hallway scene? Pure visual storytelling. The pacing does drag in the middle stretch. There’s a sense that Soderbergh likes hanging out with his characters maybe a bit more than the story demands. The actual heist—the centerpiece—isn’t quite as intricate or suspenseful as it could be. Compared to something like “Ocean’s Eleven,” which Soderbergh would direct a few years later, “Out of Sight” is way less about the crime mechanics and more about the people stuck orbiting each other’s gravity. For me, the emotional punch comes from the fact that you actually end up rooting for everyone to get away—criminals and Marshals alike. This isn’t a grim, gritty world where hope gets smothered, or a cartoon movie where stakes don’t exist. There’s always just enough danger and heartbreak to make you care, but you don’t leave the movie feeling crushed. The romantic undercurrent dodges corniness, and there’s enough noir around the edges to keep things from being weightless. “Out of Sight” isn’t perfect, but it’s got a swagger and a sense of fun that most crime movies fumble completely. It’s clever without being smug, sexy without being sleazy, and confident enough to go quiet when it needs to. Sure, the finale understates itself a little, and some of the supporting characters don’t get enough development, but at the end of the day, I’d watch this twice before sitting through another gloomy neo-noir. It’s the best kind of stylish throwback.

There’s something really special about Jackie Brown. It’s not the most talked-about Tarantino film, but honestly, that gives it some breathing room. Released in 1997, it sits quietly between Pulp Fiction’s explosive hype and Kill Bill’s stylized insanity. This one is more mature and deliberately paced. The story centers on Jackie, a tired flight attendant who gets caught up running cash for a lowlife gun runner and ends up playing a dangerous game to save herself. It’s based on an Elmore Leonard novel, which means the bones of the plot have a great snap to them, full of cons and double-crosses. The main thing that stands out is the cast. Pam Grier crushes it as Jackie. There’s a world-weariness to her performance, but also this simmering intelligence. She’s not just a pawn in the game — she’s thinking three moves ahead. Robert Forster as Max Cherry also deserves a shoutout; he brings this gentle, unflashy honesty that balances out all the schemers. It feels almost rare in a Tarantino movie to get characters who don’t talk in essays or pop culture banter every moment. Tonally, this movie feels different from Tarantino’s other stuff. It’s patient. It actually lets its scenes breathe. You can almost feel the California heat pressing in through the windows. The soundtrack doesn’t jump in your face, but it’s got soul — the Delfonics’ “Didn’t I Blow Your Mind This Time” gets a real workout, and it somehow makes everything feel both nostalgic and a little bit sad. There’s violence, but it never feels slick or glorified. The build-up to each confrontation is anxious and real. The pacing works for the story, but I won’t pretend it’s always perfect. The movie is definitely long and there is fat around the middle act. Sometimes you feel like you’re waiting for characters just to get into their cars, drive somewhere, and look tired. But underneath all that, there’s a payoff to the way the story unfolds — it’s about people who are authentic (or faking it). Tarantino flexes restraint here, which actually pushes the tension higher when it counts. Cinematography is sharp but not showy. Colors pop along the LA strip malls, and there are a lot of scenes in cheap offices and bland apartments. It’s not glamorous, but you can almost smell the old carpet. The film sticks to shots that serve the story rather than show off, which suits Jackie’s perspective. There are some clever bits — pay attention to how the camera lingers on faces during conversations. It gives space for the actors to do more than just spit dialogue. What worked for me was the emotional undercurrent. Yeah, it’s about a heist and all the double-crosses, but there’s something unexpectedly tender. Jackie and Max’s relationship, the way they circle each other with caution and regret, brings some heart to the whole messy criminal backdrop. You start really rooting for them to catch a break, which is not always the case in crime movies loaded with antiheroes. That slow dance between trust and loneliness is the movie’s real hook. Not everything lands. Samuel L. Jackson is doing his Samuel L. Jackson thing, which is fun but feels a bit like he’s playing a greatest hits album as Ordell. Bridget Fonda and Robert De Niro bring energy (and some needed comic relief), but their subplot can feel like it’s there to pad out the running time rather than advance the story. The movie’s not in a hurry and doesn’t care if you notice. If you’re coming in hoping for Pulp Fiction’s flash or Kill Bill’s blood, this might feel muted. I think that’s intentional, but I get why people can lose patience. All in all, Jackie Brown is a crime film for grown-ups who have watched too many crime films. It’s about compromise, getting older, trying to tip fate in your favor when the world isn’t going your way. There’s sly humor, soulful aches, and a sense that real life doesn’t always give you a clean exit, no matter how clever your plan. It’s not Tarantino’s finest hour, but it might be his most rewatchable. I find myself coming back to it, especially when I want crime with a little empathy.

I revisited Michael Mann’s 2004 crime thriller Collateral recently, and honestly, it’s still one of those movies that gets under my skin in the best way. Tom Cruise plays a silver-haired contract killer named Vincent who forces Jamie Foxx’s cabbie, Max, to drive him around LA for a night of hits. On paper it sounds simple, maybe even a little ridiculous. But Mann doesn’t let anything about this premise go to waste. There’s an urgency to the story that kicks in about five minutes after Vincent enters Max’s cab, and it doesn’t really let up until the credits. One of the first things you notice is how LA itself becomes more than just a backdrop - the city feels alive and dangerous, buzzing with neon lights, emptiness, and a sense of lurking threat. Mann’s choice to shoot largely on digital, which was still pretty new for big movies at the time, gives everything a weirdly intimate feel. Dark alleys, flickering bars, and endless city stretches are bathed in a kind of digital haze. It all feels immediate and real, but also a little unreal, which fits the mood perfectly. It’s stylized, but not in a way that screams for your attention; it just gets in your head. The casting here is a masterstroke. Jamie Foxx gives a genuinely nuanced performance as Max. He’s just a regular guy who gets swept into this nightmare, but Foxx doesn’t play him as a clichéd everyman. There are moments of hesitation, bursts of anger, flashes of creativity - he keeps surprising you. And then there’s Cruise, who goes fully against type. He is icy and unreadable and all sharp edges. Somehow, Cruise pulls off being menacing even when just making small talk. His Vincent is efficient and philosophical, making you uncomfortable but also a little fascinated. What really sells Collateral is the chemistry between Foxx and Cruise. The entire film rests on that dynamic. You’ve got Max’s simmering panic clashing against Vincent’s cold confidence, turning their cab rides into mini-chambers of psychological warfare. My favorite scenes are the quieter ones: two men in a car, circling conversations that say a lot about class, apathy, morality. Their exchanges are uncomfortable but mesmerizing. Mann seems to delight in long takes and awkward silences - you can almost feel LA’s night air between the dialogue. The film is tight in a way a lot of crime movies aren’t. There’s little wasted time or side quests. Sure, there’s an action set piece or two (a Korean nightclub sequence stands out - slick, violent, and both leads in over their heads), but the movie stays focused. When it does break into violence, the impact is quick and harsh, not stretched out for spectacle. This keeps the tension humming and never feels forced or show-offy. It does rely on a few coincidences that can stretch believability, which isn’t a crime movie cardinal sin, but I did find myself wishing a couple of plot turns were a little less convenient. You also have to accept that Vincent, a hyper-competent hitman, sometimes gets a little too talky for his own good. Still, the script (by Stuart Beattie) mostly walks the line between stylized and grounded, and the dialogue feels sharp. The ending… well, without giving anything away, let’s just say it lands with more of a philosophical thud than an explosive bang. For some people, that might be a letdown, but I’ve always been cool with it. By the time the credits roll, you’re left thinking less about what happened to the characters and more about what the whole ordeal meant. Collateral is more interested in questions of purpose, randomness, and city loneliness than just who survives. In the end, Collateral holds up as one of the most satisfying urban crime thrillers of the 2000s. It’s beautifully shot, well-acted, and tense as hell. It isn’t perfect - some logical leaps and a couple character beats can feel a little movie-ish rather than human - but even with its flaws, it has a mood and energy that’s hard to shake.

Animal Kingdom is a gritty Australian crime drama that grabbed me right away with its slow burn atmosphere and uneasy energy. The setup is pretty simple: a teenage boy, J, loses his mother and gets dumped into the care of his extended family, who happen to be a group of dangerous Melbourne criminals. It’s not a flashy gangster movie; it feels a bit like watching a lion’s den from the inside, where you’re never sure if the people on screen are about to hug or tear each other apart, which makes for a pretty tense ride. What really works here is the tone. There’s this constant sense of dread simmering in the background, helped by the muted color palette and some seriously claustrophobic cinematography. The director, David Michôd, uses a lot of lingering shots and slow zooms that make domestic scenes feel downright predatory. The score is minimal and icy - it creeps in at exactly the right moments. The acting is top notch, especially Jacki Weaver as the matriarch, “Smurf.” She plays her role with this unnerving mixture of warmth and cold calculation. James Frecheville as J is perfectly blank in the way a teenager totally out of his depth probably would be, and Ben Mendelsohn’s turn as the unpredictable Uncle Pope is honestly chilling. He has this dead-eyed stare that sticks with you long after the credits roll. If the movie stumbles anywhere, it’s in the pacing. Animal Kingdom takes its time setting things up, and for a while, it feels like not much is happening besides people sitting around and glaring at each other. The gradual buildup definitely pays off in the last act, but I can see some viewers finding the slow start a bit tedious or alienating. There's also an emotional distance - the movie keeps you at arm’s length, probably on purpose, which fits, but also makes it tough to fully connect with anyone on a gut level. Also, while the story is loosely based on real events, it doesn’t dwell on realism for realism’s sake. The criminal schemes and family betrayals play out in a way that’s believable, but not overly explained, so a lot of tension comes from just piecing together what’s going on. That ambiguity can be a strength, but it occasionally left me wishing for just a bit more backstory or motivation. Overall, Animal Kingdom isn’t for people looking for a parade of gunfights or Ocean’s Eleven style shenanigans. But if you like your crime dramas more psychological - think less heat, more slow-burn unease - it’s absolutely worth your time.

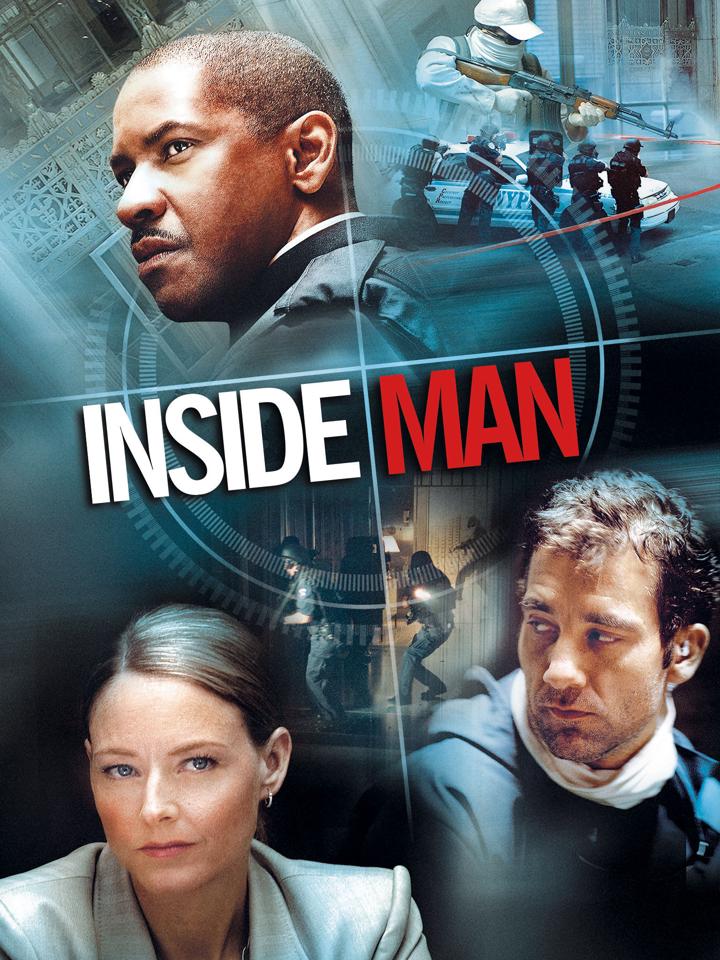

Spike Lee’s Inside Man is the kind of stylish bank heist thriller that plays by the rules and then decides to mess with you for fun. Denzel Washington is front and center as the detective in charge of a bank standoff, and he brings enough wit and subtle bravado to keep you glued, even if you think you know how these stories go. Clive Owen is the even-cooler opponent, masked up and philosophical in that “I’m smarter than you” criminal way. The movie jumps between real-time negotiations and tantalizing flash-forwards that hint at something way bigger. Visually, it's a treat. There’s this crisp cleanness to the camera work that makes NY look both lived-in and quietly menacing - Lee never lets you forget the city matters here. The editing is super tight too. Every cut feels deliberate, ramping up the tension without ever going into shaky-cam overload. And the Marvin Gaye drop early on? Instantly iconic. Jodie Foster is maybe the weirdest, most fascinating part of the cast. She’s icy, enigmatic, and strolling through the movie like she’s got a secret the director never let the rest of us in on. The best scenes are the verbal chess matches between Denzel and Foster, two characters who probably hate each other for how much they recognize the same greatness. Willem Dafoe pops up too, but honestly, he feels underused - when you’ve got Dafoe, you want more chaos. The script’s got an efficient, twisty backbone, but it’s less about explosions and more about testing your brainpower. Even if you can unravel one twist, the film throws in just enough smoke and mirrors. There are social and racial undercurrents all over; Lee sneaks in commentary about post-9/11 New York, bias, and privilege. It’s all blended in so smoothly that the movie manages to be thoughtful while still just being fun and pulpy. My only real beef is the ending feels just a little too tidy. It tries to give every character what they “deserve,” but the movie loses some of its edge in the final moments. I wanted a slightly messier conclusion - instead, it bows out with style but maybe not enough bite. Still, Inside Man holds up shockingly well nearly two decades later. It’s a heist movie that gets your heart racing, but also one that asks you to pay attention, pick sides, and reconsider by the end who actually won. Never boring, often clever, and enough Denzel to make you wish he solved every crime.

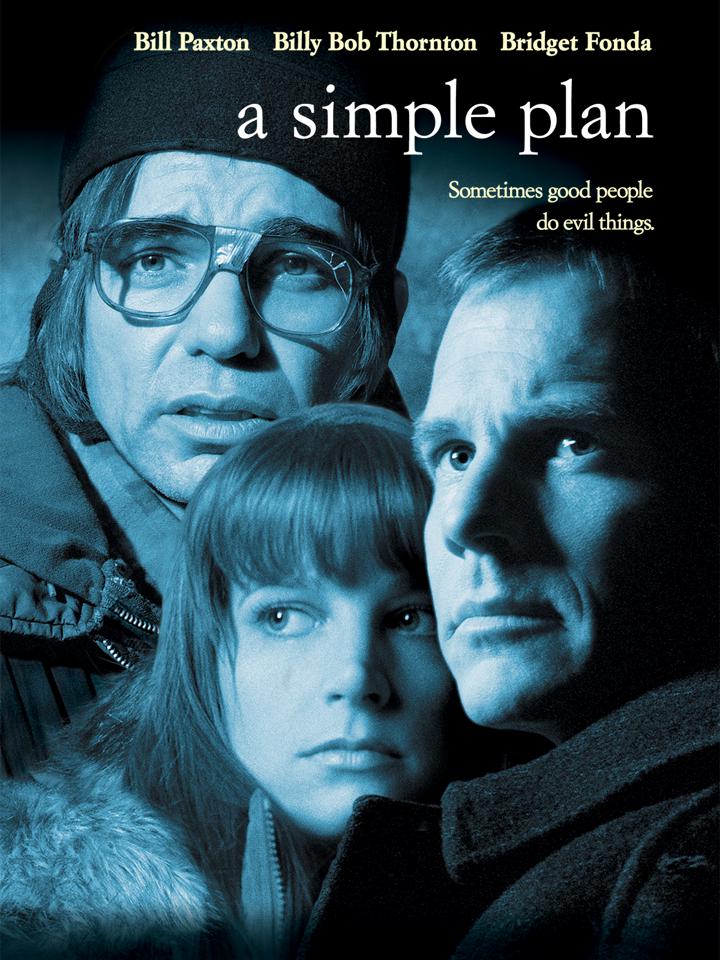

This film is a slow-burn crime thriller about three ordinary guys who stumble upon a crashed plane full of cash in the snowy woods of Minnesota. It starts innocently, with the friends convincing themselves they’ll wait to see if the money is claimed, but things spiral fast. The tension builds around how far regular people will go to protect a secret, and it’s the sort of story that quietly sneaks up on you, gnawing at your conscience. What stood out the most to me was how grounded everything felt - no flashy editing or over-the-top action. Director Sam Raimi keeps your attention locked on the moral unraveling of each character, especially Hank, played by Bill Paxton in maybe his best, most relatable role. Billy Bob Thornton is heartbreakingly good as his simple-minded but trusting brother, making it so hard not to root for them even as they dig themselves deeper. It isn’t a flawless film; the pacing is deliberate, and if you’re expecting a twist-filled crime caper, you’ll be disappointed. Sometimes the dialogue veers just a little melodramatic, and there are a couple of scenes where character motivations didn’t totally click for me. Still, you can’t look away, and the bleakness of the snowbound setting adds so much to the tension. Visually, the cinematography is quietly gorgeous - there’s a bleak poetry to those endless grey skies and the stark white snow. The camera lingers just long enough to let you soak in the isolation, amplifying the characters’ paranoia. It never looks slick, which fits perfectly with how the story unspools - messy, raw, and pretty unforgiving. You would enjoy this if you like crime stories that feel real, where small-town desperation and good intentions clash with temptation. If you’re in the mood for something that works more like a moral fable than a typical thriller, and you’re okay with a slow build, A Simple Plan is a hidden gem.

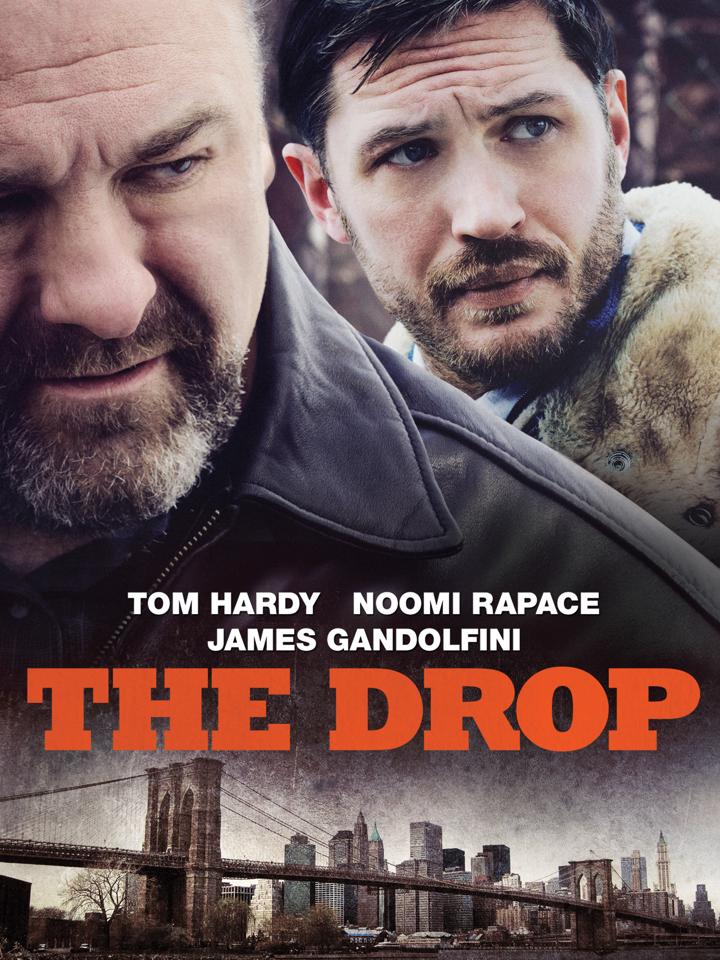

So, "The Drop" is this cool little crime drama from 2014 that somehow slipped under a lot of radars. It’s set in Brooklyn and follows Bob Saginowski, a quiet bartender (played with this understated strength by Tom Hardy), whose bar is actually a drop point for local mob money. The film starts off like a mellow slice-of-life but builds into something darker, mostly thanks to a robbery gone wrong and the complications that spiral out from there. What really stands out is the film’s mood. Director Michaël R. Roskam keeps things tight and quiet, almost like a simmering stew. It’s not constantly explosive or heavy on action, but there’s a tick-tick-ticking sense of danger underneath even the most mundane scenes. Brooklyn looks cold and almost claustrophobic - the cinematography makes you feel the chill and grime of the neighborhood, which pairs perfectly with the somber story. The acting is honestly what makes this worth seeing. Tom Hardy completely transforms into this guarded, somewhat damaged everyman, and James Gandolfini, in his final film role, brings a weighty, world-weary presence as Bob’s cousin. Noomi Rapace is here too, adding a vulnerable edge, and the supporting cast delivers, even in smaller roles. No one's chewing scenery, but the subtlety works in the film’s favor. If there’s a drawback, it might be how slow and subdued everything is. If you’re coming in expecting the typical crime-thriller fireworks, this could feel a little too measured or reserved. Some plot points (mostly involving side characters) don’t get as much payoff as you’d hope, but for me, the ending wraps things up in a way that’s both haunting and oddly satisfying. You would enjoy this if you like character-driven stories where the tension comes from the unspoken, and you appreciate crime films that are more about mood and psychology than big twists or shootouts. Think early ‘90s Scorsese but quieter, or if you liked "The Friends of Eddie Coyle" or "A Most Violent Year."