Browse our collection of drama reviews and ratings.Showing 12 of 75 reviews.

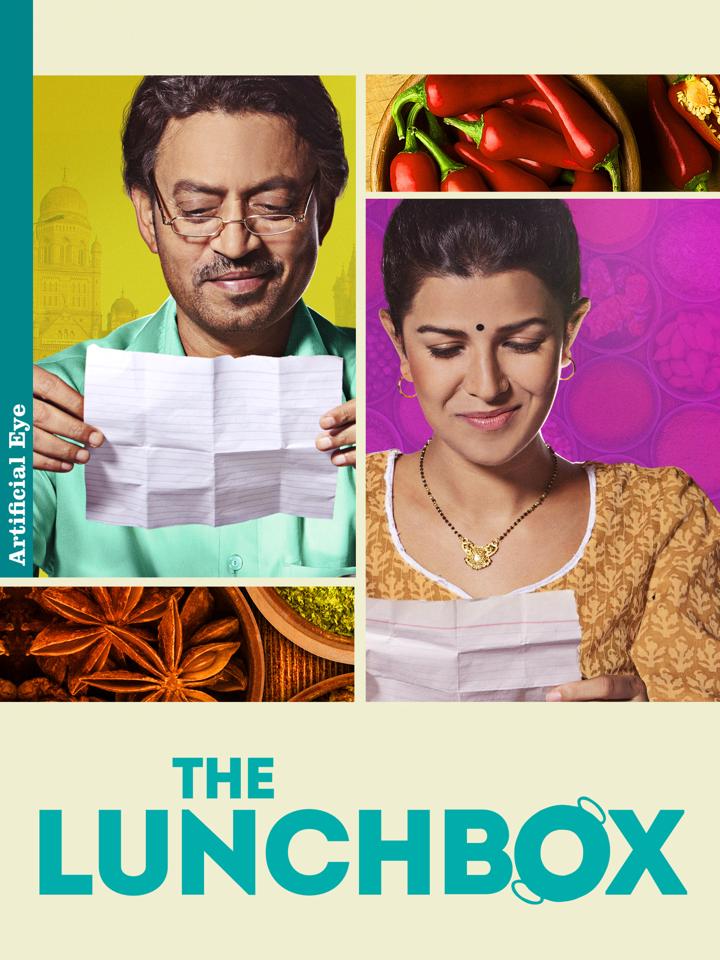

This is such a quietly affecting film from India that easily gets overlooked but really deserves way more love. “The Lunchbox” centers around an accidental exchange of lunchboxes in Mumbai—an unlikely mistake that sparks a kind of pen-pal romance between a lonely widower nearing retirement (Irrfan Khan) and a neglected housewife (Nimrat Kaur). The film manages to turn these small, everyday routines into something almost poetic, and it’s all so subtle that you barely even notice how invested you’ve become. What stood out for me was the way director Ritesh Batra uses silence and unspoken gestures; you feel so much tension or excitement in a look, a sigh, or the way food is prepared. The food itself almost becomes a character! The cinematography is simple but incredibly effective—the bustle of Mumbai, cramped apartments, and the randomness of the city’s lunch delivery system all help build this believable, lived-in world. Irrfan Khan, as always, is wonderful—he brings a kind of gentle sadness and dry humor to his role, and his chemistry with Nimrat Kaur is mostly delivered through handwritten notes rather than shared scenes. That said, I wished Nimrat Kaur’s storyline got a bit more breathing space; there are hints of deeper struggles that I would have loved to explore more. The pacing can be a little slow at times, but I found myself appreciating the film’s patience rather than getting bored. It doesn’t try to resolve everything in neat little bows, which I actually found refreshing. If you like stories where not everything goes as planned, and people just… keep living, mistakes and all, this fits the bill. There’s also a wonderful supporting turn by Nawazuddin Siddiqui, who brings levity and a bit of unpredictability to the otherwise restrained tone. You would enjoy this if you love quiet, character-driven dramas that unfold at a languid pace, or if you’re into films like “Lost in Translation” or “Paterson” where the little moments say everything. It’s a film about loneliness, connection, and second chances, and it lingers long after it’s over.

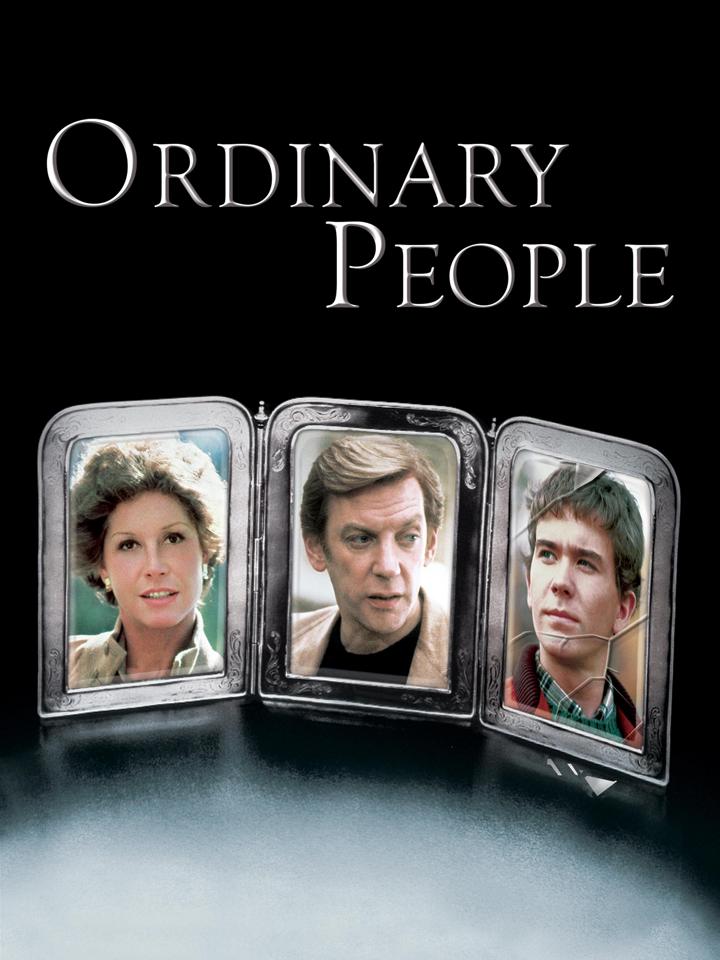

I finally got around to watching "Ordinary People," and I have to say my expectations were complicated going in. It has that daunting Best Picture reputation, but on the flip side, it never quite became a pop culture touchstone like some of its Oscar peers. The story centers on a suburban family quietly self-destructing after the older son's tragic death and the younger son's attempted suicide. It's tight, restrained, and unfolds in a way that’s intimate but never showy. What hit me immediately was the tone. It’s raw but not in the gritty, in-your-face sense. Instead, everything simmers just below the surface. Robert Redford directs with a sort of gentle distance, almost clinical at times. He leans hard into chilly silences and lingers on the smallest expressions, so you feel every awkward dinner or loaded pause — it all feels uncomfortably real. That restraint is both a strength and a limitation: sometimes I wanted the movie to push harder, to let emotions boil over. The acting, though, is a big part of why the movie works. Donald Sutherland is all nervous energy and awkward kindness as the dad, and Mary Tyler Moore is simply crushing as the brittle, emotionally armored mother. She’s maybe the most tragic part of the movie because you can see every feeling bottled up so tightly it hurts to watch. Timothy Hutton, as Conrad, the surviving son, is quietly heartbreaking. There’s a therapy scene early on where he cannot even look at the psychiatrist, and the way his voice cracks around basic questions really got under my skin. Judd Hirsch plays the therapist, and while his “caring adult with quirks” role is a bit dated by today’s standards, he gives Conrad’s journey some breathing room. The movie is visually subdued, leaning into beige suburban interiors and fall colors. This works thematically — the blandness of the set speaks volumes about the family’s attempts to keep life “normal.” But let’s be real, it can get a little visually numbing after a while. I found myself craving even one overt stylistic risk or color pop to break the monotony. That said, some moments really land, like the scene of Conrad alone in the kitchen, shot in soft morning light, which says more about isolation than a dozen lines of dialogue. Pacing-wise, "Ordinary People" is definitely on the slower side. I was surprised how much of the runtime is deliberate, almost meditative. There are lots of one-on-one conversations, and sometimes you’re just sitting with a character’s discomfort for a full minute. I get that it’s being true to the process of grief and gradual healing, but it does toe the line of feeling stagnant, especially in the second act. If you like tight plotting, you’ll probably be frustrated here. One of my bigger gripes is that the film shies away from really holding the parents (especially the mother) accountable in a satisfying way. There’s a ton of empathy, but I sometimes wanted the writing to dig further into the roots of the family’s dysfunction — it lets certain characters off the hook, or at least lets their pain fester without much hope for insight. This isn’t a knock on Moore’s performance, which is outstanding, but more a critique of how safe the script plays it. Still, the emotional impact is hard to deny. The movie nails what grief does to family dynamics, how it makes everyone slightly alien to each other. Even the awkward little moments — like a half-hearted “goodnight” in the hallway or a missed handshake — feel heavy. When it does go for an emotional release, it lands, maybe because you’ve had to sit with that tension for so long. Returning to it so many years later, "Ordinary People" feels like a bit of a time capsule. It’s not flashy. It’s not fun. But it is honest, and it pays close, sometimes painful attention to the ways people break under pressure. It’s a drama for people who can handle discomfort. That’s probably why, decades later, it still packs a punch, even if it’s more of a slow bruise than a knockout.

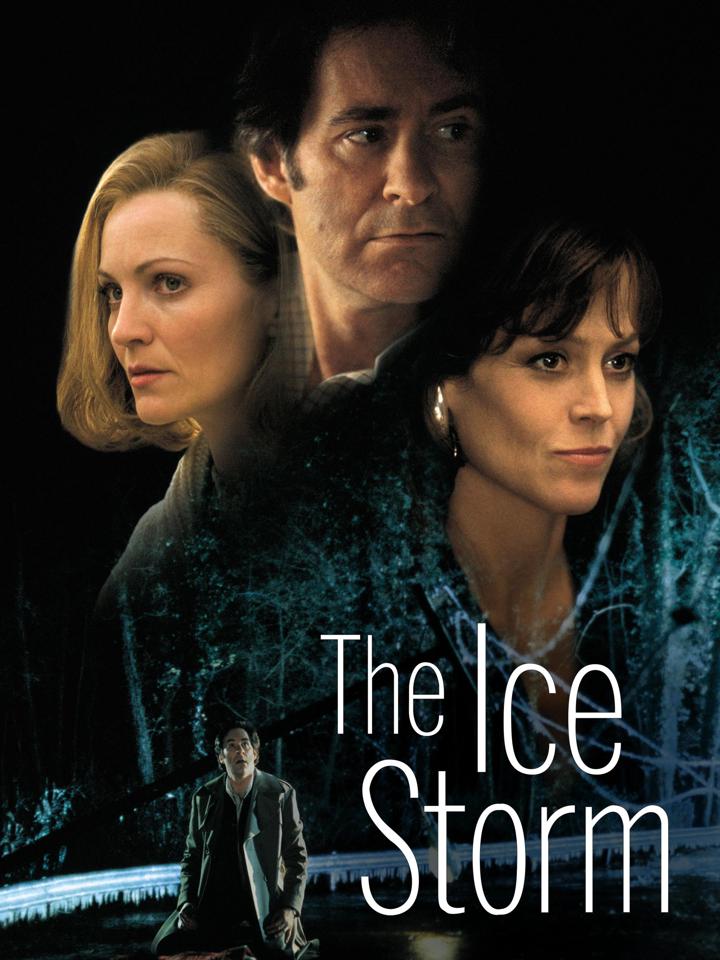

Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm is one of those films that lingers in your head for days, partly because it never quite lets you get comfortable. Set in a well-to-do Connecticut suburb in 1973, the movie dips into the tangled lives of two neighboring families during a single very cold Thanksgiving weekend. The setup is deceptively calm: picture-perfect homes, plenty of plaid, but beneath it all you know something’s beginning to crack. Lee doesn’t just set the film during an actual ice storm — he uses it as a metaphor for emotional frigidity, miscommunication, and the slow erosion of intimacy. The cast is almost comically stacked in retrospect: Kevin Kline, Joan Allen, Sigourney Weaver, Tobey Maguire, Christina Ricci, and Elijah Wood, just to name the core. What stands out is how lived-in all the performances feel. Weaver is a particular highlight as Janey Carver, radiating both a world-weariness and simmering resentment with the quiet confidence that makes her character both unlikable and irresistible. Joan Allen’s turn as Elena is quietly devastating — she’s brittle and beautiful, barely holding it together while keeping up appearances. Every actor seems perfectly dialed into the subdued panic that makes suburban malaise so potent on screen. One thing that sets The Ice Storm apart from other family dramas is its refusal to judge. These are people who lie, cheat, and ignore their children, but Lee and screenwriter James Schamus don’t punish them or paint heroes and villains. Instead, the film lingers in the awkwardness of their mistakes. There is no big Oscar-bait monologue, no cathartic resolution, just shivers of realness that hurt more because they’re so recognizable. The film’s parties, conversations, and even the sexual encounters are awkward to the point of squirm-inducing, and it feels exactly right for these characters. The production design is meticulous in a low-key way. No pin-neat Mad Men sheen here — the houses are cluttered, the wood paneling is a little too dark, everything feels oppressively cozy rather than magazine-worthy. Cinematographer Frederick Elmes shoots a lot through frosted glass and perched behind corners which gives the sense you’re listening in on secrets or spying from the hallway like a kid. There are a couple of breathtaking shots of the icy landscape — you can almost feel how numbingly cold it is outside, both literally and between these characters. Pacing is maybe the only real issue. The middle third can get a little bogged down in glum repetition, which I imagine will grate on some who crave a cleaner dramatic arc. There are a few scenes that feel like the movie is more interested in period detail than pressing the story forward. Still, I think that’s part of Lee’s point — the emotional paralysis traps everyone in their own drifting routines. The script refuses to spell things out. Instead, it drops you into these small, awkward moments between parents and kids, or husband and wife, and trusts the audience to put things together. For some, it’s going to feel a little chilly in tone — I kept thinking, “Man, is anyone going to actually talk to each other here?” — but there’s power in the longing and missed connections. The best example is Maguire’s Paul, adrift at prep school and even more lost at home, fumbling his way through feelings he can’t express. The soundtrack hums along quietly in the background, full of appropriately melancholy 1970s cuts but mercifully never shouting the era at you. The film is full of silences and weirdness — a scene in a key party where Allen’s character can barely force herself to make a choice, or Ricci’s Wendy ransacking a neighbor’s medicine cabinet with a strange little curiosity. These aren’t people anyone would aspire to be, but Lee finds compassion for how lonely and confused they all are. The Ice Storm is probably not for everyone — it’s pretty bleak, and if you’re allergic to family dramas where people mostly suffer in silence, this won’t convert you. Still, it’s a huge achievement in showing both the pain and absurdity of people who don’t know how to reach out. You walk away with this weird ache and maybe a strong urge to call your parents. It’s cold, but it’s honest, and sometimes a truth this chilly feels weirdly comforting.

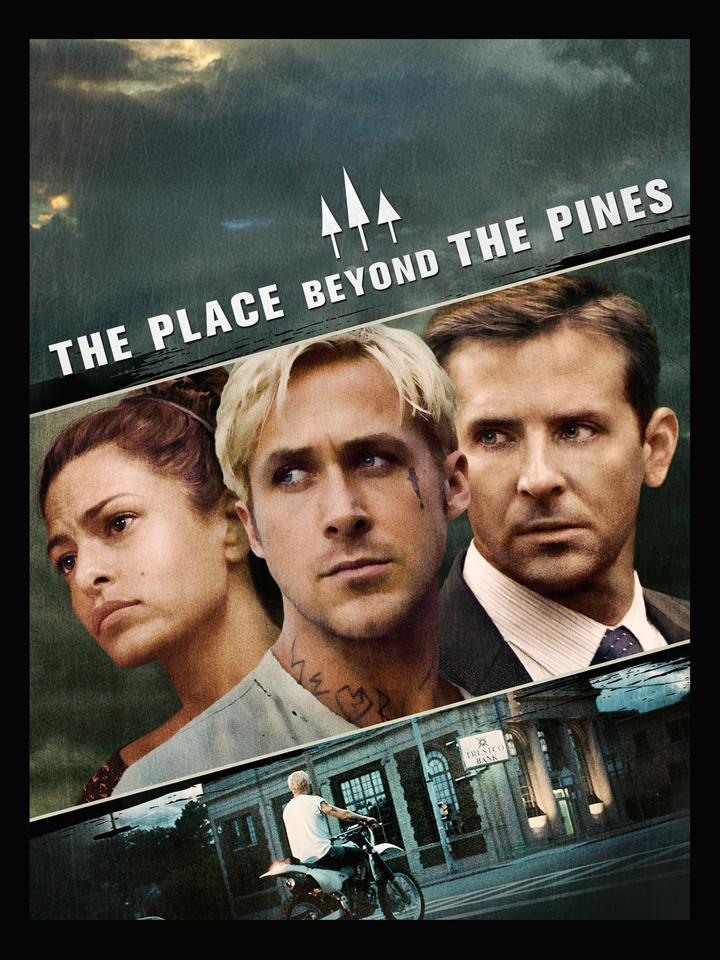

The Place Beyond the Pines is the sort of drama that sticks with you, not just because of its ambitious narrative or brooding atmosphere, but because it is genuinely trying to dig a little deeper into fathers, sons, and the cycles we get trapped in. Released in 2012, it’s not exactly a household name, but among movie nerds, it’s a solid recommendation for when you want something meatier than your standard crime drama. The film is basically split into three interconnected parts, each focusing on a different character, and it’s the kind of structure that could have been a disaster, but here, it mostly works. Ryan Gosling sets the tone right out of the gate. He plays Luke, a stunt motorcycle rider with a face full of tattoos and a talent for quiet menace. From the start, Gosling is magnetic. His dialogue barely fills half a page, but every look and mannerism feels loaded. When he discovers he has a son he never knew about, the film pivots into this gritty, desperate portrait of a man trying to do the right thing by doing all the wrong things. The way Gosling’s performance undercuts all the tough-guy posturing with vulnerability is what keeps the first third from just feeling like Drive v2, but with more bank robberies and forest roads. Then the focus jumps to Avery, played by Bradley Cooper, and the movie almost becomes a different film for a bit. Cooper is quietly excellent, playing a rookie cop navigating this minefield of corruption in his department, plus the tension with his own family. He’s clean-cut and smart, but the film never lets him off the hook for the choices he makes. I remember being surprised by how tense all these scenes were, especially the shootout early on. You can really feel how director Derek Cianfrance is pushing his actors to dig into so much regret and moral ambiguity. The cinematography is the other star here. There’s this almost dreamy haze over the whole movie — lots of tall pines, muted colors, and that upstate New York melancholy. The camera rarely sits still, giving chase scenes and even simple conversations this nervous energy. Sean Bobbitt, who shot Shame, brings that same intimacy and grit. The opening long take, following Gosling through a grimy fairground, is pretty breathtaking and honestly better than most action scenes with three times the budget. But the movie isn’t perfect. The ambition sometimes outweighs the execution, especially in the third act when the timeline jumps forward by fifteen years. Suddenly, we’re watching the sons of the two main characters, and things lose a bit of the emotional punch found earlier. While Dane DeHaan and Emory Cohen bring plenty of energy, their arcs feel mildly rushed and, at times, a little forced — like the script is working overtime to tie everything up in a neat-ish bow. What absolutely works, though, is the sense of consequence. The Place Beyond the Pines doesn’t let characters off easy, and even when the pacing drags, you’re invested in the fallout. The movie lingers on what happens when people live with the aftermath of a single bad day. Eva Mendes is terrific as Romina, quietly devastating in all her scenes, and honestly, she deserved more of the spotlight. Something about her restraint makes her brief appearances hit harder than some entire movies built around similar characters. The tone here is heavy, fairly bleak, and it’s not afraid to take its time. There are definitely stretches that could have been trimmed, but it never devolves into melodrama. There’s an authenticity to how the film deals with guilt and legacy. It reminded me a bit of Eastern Promises in how it presents that intersection of family and crime, except with more Americana and less violence up front. The Place Beyond the Pines isn’t flawless. Some viewers will call the last act messy or uneven, and I won’t argue. But it’s a rare modern drama that feels just as invested in its silences as its explosions. If you like grounded, atmospheric films that actually care about character and consequence, this one is worth a night. You might even find yourself thinking about your own family history — not every movie has that kind of sting.

If you haven’t checked out “A Most Violent Year” yet, you’re definitely not alone. This 2014 drama flew pretty under the radar, at least compared to the explosion-heavy Oscar hopefuls released that season. But here’s the thing: this is one of those quiet, tightly wound films that worms its way under your skin and stays there. It’s set in New York City in 1981, which just happens to be the city’s statistical high point for violent crime, and follows Abel Morales (Oscar Isaac), an ambitious heating oil businessman trying to expand his company while violence and corruption threaten him from every angle. The mood is almost bone-chillingly tense — not because there are shootouts every ten minutes, but because director J.C. Chandor knows how to build anxiety out of silence, slow zooms, and conversations where everyone is hiding something. There’s a calm menace to almost every interaction. The palette is muted, lots of greys and browns, and you can almost feel the cold city wind whistling through the film’s empty winter streets. It’s atmospheric to the max, but never in a flashy way. Oscar Isaac gives what I honestly think is his best performance to date. He channels a real Al Pacino-in-Godfather vibe — all measured intensity and unwavering calm, even when he’s obviously screaming inside. What really got me is how relatable his ambition is. He wants what he’s earned, but he’s hemmed in by a system that rewards people for cutting corners and getting their hands dirty, which is not his style (or so he claims). Jessica Chastain backs him up as his tough-as-nails wife Anna, and while she dips into the hard-edged mob-wife thing a little too deeply at times, it’s still a killer performance and their chemistry is magnetic. The story moves at a deliberate pace, sometimes to a fault. There are moments when the plot feels like it’s circling, almost getting bogged down in legal procedures, union meetings, and the logistics of importing oil. It’s obviously intentional; Chandor wants you to sit with the anxiety of the whole world closing in, but if you’re not in the mood for slow-burning dread, you might get restless. I’m usually pretty patient, but even I felt my attention wandering a bit around the midpoint. What the film nails, though, is its sense of place. The movie absolutely nails what New York can feel like in the dead of winter — all grey skies and dirty snow, long shadows and nervous glances. The cinematography by Bradford Young is just gorgeous. There’s one shot of Oscar Isaac running through deserted train tracks at dusk that’s still stuck in my head years later. Light and shadow do a lot of heavy lifting here, filling in psychological gaps where dialogue is minimal. Another thing I appreciated is how the movie refuses to let its main character off the hook. Abel isn’t a straight-up hero, and the film doesn’t really ask you to root for him so much as watch him squirm. For a story that’s supposedly about morality, there’s a ton of ambiguity. Everyone — even the supposed “good guys” — grabs for an advantage wherever they can. You end up questioning where the ethical lines really get drawn, or if they ever matter when survival’s at stake. If I had to nitpick, the movie could have pushed a bit harder in terms of big emotional payoffs. There are moments where I wanted someone to finally crack, just once, and really let loose with the anger, the terror, the hurt. Instead, everything stays buttoned up and reserved. That’s likely a conscious character choice, but it leaves the film feeling a bit chilly and remote at times. You empathize, but you don’t always feel it in your gut. Overall, “A Most Violent Year” is for anyone who loves a slow-burn character study with an edge of danger and moral complexity. It’s beautifully made and masterfully acted, even if it sometimes keeps its characters a little too tightly in control. Is it pulse-pounding? Not often. But if you’re willing to sink into its icy vibe and subtle tension, it’s a quietly gripping watch.

I’ll admit I was a little late to the “Marriage Story” party, mostly because the whole “divorce drama” premise sounded like homework. But Noah Baumbach pulls off something strangely intimate and true here, shunning melodrama for the messier middle ground of what actually happens when people grow apart. The film is bookended by two heartbreaking, quietly stunning monologues that set the stage for a breakup you can’t look away from. The acting here really is next level. Everyone talked about Adam Driver’s wall-punching scene, and honestly, it deserves the hype - he nails that thin line between control and total unraveling. But I think Scarlett Johansson matches him beat for beat. She gives Nicole so much dignity and everyday pain with a performance that never once slips into “movie divorcee” cliché territory. Visually, the film is clean and never flashy, with Robbie Ryan’s cinematography keeping the camera eerily close during uncomfortable conversations. There’s this almost unspoken tension in the way New York and LA are framed - the spaces reflect how the characters are drifting, both physically and emotionally. It sounds artsy, but it works. The pacing can be weirdly languid; there are some scenes (especially with the lawyers, even with Laura Dern chewing the scenery) that almost overstay their welcome. But it’s balanced with small, honest moments: a song at a piano, a dumb minor injury, a Halloween night that sneaks up on you with unexpected feelings. Baumbach doesn’t offer any easy answers or villains, which I love. It never feels like it’s picking a side, even if you end up sympathizing with one (and probably changing your mind as you go). The dialogue is sharp - sometimes painfully so - but also funny in the way that your own life can surprise you mid-crisis. Final point: this is not a chill Sunday watch, but if you’re up for feeling a bit raw and then spending the evening staring at the ceiling, “Marriage Story” is worth your time. I think it sticks with you because it recognizes the damage we do to each other doesn’t always make sense, even when it’s done with love.

Let me just say upfront, this movie isn’t exactly what you throw on to cheer yourself up after a rough week. “Manchester by the Sea” is heavy, and it doesn’t apologize for piling the weight on your chest. It’s this kind of quiet New England drama that feels like real life, just with slightly more poetic dialogue and a lot more heartbreak. It follows Lee Chandler, a man who is forced to face the family and town he’d rather leave behind, and it doesn’t flinch from painful emotions. What I love most is how real it all feels. Kenneth Lonergan's direction is like holding up a mirror to small-town grief - awkward, bumbling, and sometimes even funny in a way you almost feel wrong for laughing at. There are some scenes, like the bits in the police station or at the kitchen table, that just ring uncomfortably true if you’ve ever experienced a loss you couldn’t put into words. Casey Affleck is the quiet spike in the heart of all this. His performance is loaded without ever feeling showy. He walks around like the ghost of his younger self and there are scenes where you swear you can read a whole novel of regret in the way he grips a doorknob. Michelle Williams, though she’s not in a ton of the movie, has one absolutely knockout scene that twisted my stomach into knots. They never milk the moments for drama, which somehow makes it more devastating. I will say, this movie can be punishing in its pacing. It’s deliberate, which is a polite way of saying the first hour moves like slowly dripping molasses. Some people might check out before the really emotional stuff hits. If you’re not here for “sad people quietly folding laundry and staring into space,” this might test your patience. On the technical side, the cinematography is kind of sneaky good. There are a lot of understated shots of snowy Massachusetts streets and empty living rooms that do a lot of heavy lifting. Lonergan never oversells the bleakness. He just lets the gray winter light do the talking. The music is sparse but perfectly chosen, which means when it swells, you feel it right in your bones. Overall, “Manchester by the Sea” works because it doesn’t offer any easy answers or big redemption arcs. Life goes on, pain lingers, and sometimes people just can’t get better. It’s not a movie for everyone, but it’s the kind of film that sticks with you for days, poking at your own quiet heartbreaks long after the credits roll.

I’ll be honest: The Station Agent is one of those understated movies that sneaks up on you. Released in the early 2000s, it stars Peter Dinklage way before Game of Thrones made him a household name. The premise sounds almost absurdly simple. Finbar (Dinklage) inherits an abandoned train depot in rural New Jersey and moves there to be alone. Naturally, he meets a handful of persistently friendly (and sometimes odd) townsfolk who resist his attempts to keep to himself. One of the movie’s best tricks is how it builds genuine connection without feeling manipulative. The tone is reserved and sometimes wry, never trying too hard. There’s no melodrama here. It’s a drama that’s actually quiet enough for you to notice every awkward pause, every genuine smile, and every moment of someone not knowing what to say next. It feels closer to real life than most movies in this genre. Dinklage is quietly magnetic as Finbar. He says very little, but when he does, you care. Patricia Clarkson (as a grieving artist) and Bobby Cannavale (as a persistent food truck guy) are both totally charming in their own weird ways. The chemistry between the trio isn’t showy, but it feels lived-in. Clarkson, in particular, nails that combination of warmth and raw nerves. These are not polished Hollywood performances; they feel like people you could actually run into at a train stop. The small-town setting is perfectly shot - a little drab, often overcast, with slow, unhurried pacing. It won’t be for everyone. If you’re used to movies that move in big, cinematic gear shifts, you’ll wonder if anything is happening at all. But the attention to detail in each frame gives the place a sort of quiet dignity most films wouldn’t bother with. If I had to nitpick, the story sometimes sticks too closely to indie film tropes. There are a few moments where you can almost see the script itself trying to say something “deep,” and not every subplot lands equally. But when everything works, it feels honest. This isn’t a movie about grand transformation; it’s about small shifts, tiny cracks opening up where light gets in. All in all, The Station Agent is a slow burn, but the payoff is worth it if you have some patience. It trusts you to notice the little things - and if you do, you’ll come away feeling oddly hopeful, even if nothing is tied up with a neat bow.

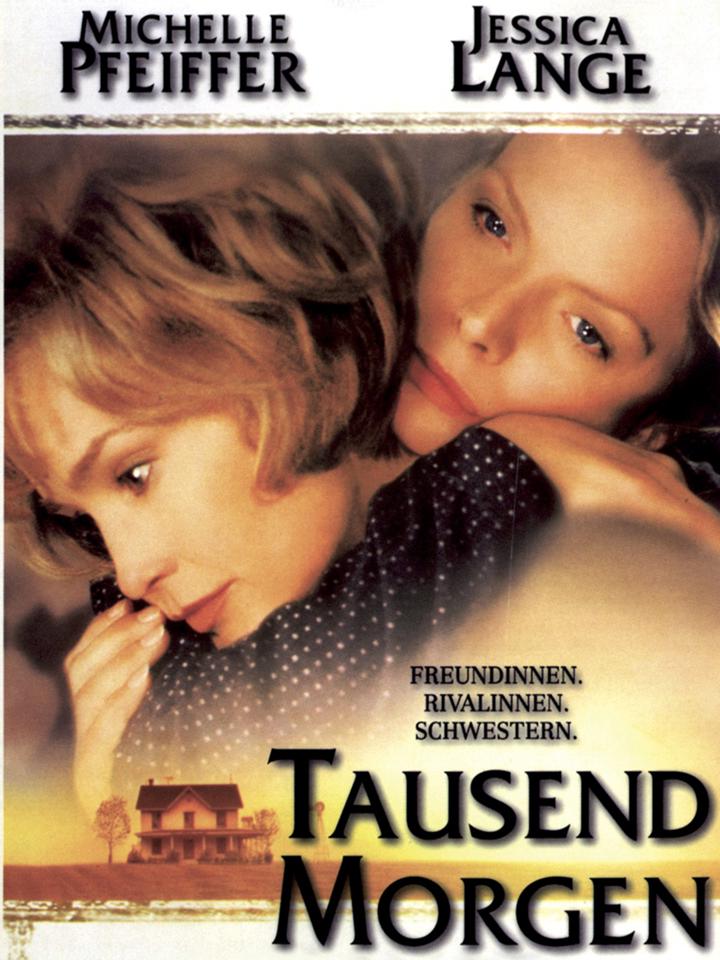

This is one of those dramas that kind of snuck past mainstream radar in the late '90s. "A Thousand Acres" is a sweeping, somber adaptation of Jane Smiley’s Pulitzer-winning novel, set against the vast, windy farmlands of Iowa. At its heart, it’s about a family stretched to breaking by buried secrets and the fallout of a father (played by Jason Robards) deciding to pass his land down to his three daughters. The setup feels like a modernized "King Lear" - which it is, sort of - but don’t let that scare you if Shakespeare isn’t your thing. What really grabbed me was the unnerving slow burn of family dynamics. Jessica Lange and Michelle Pfeiffer have a lived-in closeness as sisters spinning apart, and their performances are quietly devastating, especially as resentment boils over. The movie doesn’t flinch from the bleakness of rural isolation or generational trauma - it can be a heavy watch, but it’s anchored by these complex, believable women. The scenes between Lange and Robards are particularly raw, and there's an undercurrent of anger and grief that feels authentic. The pacing isn’t always perfect. Some sections feel stretched thin, and it lingers on certain story beats a little too long, maybe to drive the point home. There are moments when the drama feels a bit melodramatic, like it wants to make each confrontation thunderous, but the script doesn’t always earn those fireworks. Still, overall, it’s honest enough that you let a few uneven moments slide. Visually, the cinematography is surprisingly lush for a farmland saga. There’s a lot of broad, golden fields, quietly beautiful sunsets, and a sense that the land itself is a character (almost stifling in its constancy). The camera lingers on long, empty highways and huge, open skies, putting you right in that atmosphere of lonely Americana. It reminded me how powerfully the backdrop of a place can weigh on a story. You would enjoy this if you’re drawn to serious family dramas with emotional weight, or if you appreciate stories about complicated women weathering the storms of legacy and loss. It’s not a light movie, but it’s rewarding if you like digging into messy relationships and rural Americana. Great for fans of “August: Osage County” or even more grounded “Big Chill” types who don’t mind a little darkness.

This is a drama about five days in 1996 when Rolling Stone journalist David Lipsky (played by Jesse Eisenberg) follows renowned author David Foster Wallace (Jason Segel) at the end of his Infinite Jest book tour. What anchors the film is the rich, searching conversations between these two men - it's like eavesdropping on a series of thoughtful, confessional late-night talks, the kind you have on a long drive with someone fascinating but mysterious. Segel's performance as Wallace gently surprised me; he brings so much awkward sincerity and fragility, straying far from the comedic roles you might know him for. There’s an early diner scene where Wallace ponders junk food and loneliness at a suburban table - it's funny, strikingly honest, and sad all at once. The film leans on dialogue, and while that's mostly its strength, it can sometimes feel a little stagey or as if it's more for people who love listening rather than watching things happen. This is absolutely for those who are drawn to character studies, movies made of smart conversation, and anyone curious about writers and the messy lives behind big novels. If you’re after action or sweeping visuals, this won’t be your thing. But if you love films that make you think about your own weird relationship with fame, creativity, or even just companionship, this will quietly resonate.

Columbus is a quiet, beautifully-shot indie drama from 2017 about a young man and a local woman who cross paths in Columbus, Indiana - an unlikely modernist architecture mecca. John Cho plays Jin, in town unexpectedly due to his estranged father’s illness, and Haley Lu Richardson is Casey, a library worker stuck at a crossroads. The film doesn’t rush to force a plot, instead letting the conversations and awkward silences breathe alongside the striking buildings that fill every frame. What gripped me was how carefully director Kogonada frames both the city and the characters - there’s a deep sense of yearning that floats through each scene. Richardson, in particular, absolutely shines; there’s a sequence where she talks about one of her favorite buildings, and you can actually feel the weight of her dreams and regrets in her voice. It’s understated, gentle, but never dull; the film trusts the audience to soak in what isn’t said as much as what is. If there’s a flaw, it’s that Columbus asks for a lot of patience. Some scenes linger long after you think they need to, and if you crave big moments or pace, you might drift away. But if you like meditative films like Lost in Translation or Before Sunrise, and find solace in thoughtful conversation and evocative imagery, this will absolutely land for you.

Succession is a razor-sharp drama about the power struggles within the Roy family, who run a media conglomerate. It’s basically a modern Shakespearean tale, but with private jets, boardrooms, and some of the most cutting insults I’ve ever heard on TV. The show pulls you in immediately with its dark humor and icy detachment, but what really hooked me was watching all these deeply flawed, emotionally stunted characters vie for their father’s approval and their own slice of power. What stood out is the writing - it’s acidic, funny, and painfully honest. The performances are top-notch, especially Brian Cox as the formidable Logan Roy, and Jeremy Strong’s committed, jittery take on Kendall. There’s a specific moment, in the finale of season two, where the tension is so thick you practically stop breathing, and scenes like those stick with you long after. The show manages to balance cringe-inducing awkwardness with genuine heartbreak, and it’s just as fascinating watching these people fail as it is watching them win. On the downside, the unrelenting cynicism can feel exhausting after multiple episodes, and sometimes the characters’ nastiness tips into unbelievable. Unlike more optimistic shows, Succession’s world is pretty bleak - there’s not much hope for the Roys. Still, if you like your television sharp, witty, and unafraid to dig deep into family dysfunction, you’ll find it totally addictive.