Browse our collection of war reviews and ratings.Showing 12 of 19 reviews.

Kajaki is one of those war films that quietly sneaks up on you. It's based on a real-life incident in 2006, where a group of British soldiers in Afghanistan became trapped in a dry riverbed filled with hidden landmines. The entire film is set across just a few hours, but the tension is so meticulously crafted that you barely notice the minimal locations — it’s all sweat, sand, and steadily mounting dread. What really hit me is how the movie sidesteps explosive battle scenes in favor of gut-turning suspense and brutally realistic depictions of injury. There’s a lot of focus on the soldiers’ camaraderie, the black humor that creeps in as they try to steady their nerves, and the excruciating decisions they’re forced to make. This intimacy makes even small setbacks feel momentous, and the cast — filled with mostly unfamiliar faces — does an incredible job selling the authenticity. Where Kajaki doesn’t quite land is in its pacing for the uninitiated: it doesn’t hold your hand through military protocols or character backgrounds. For a casual viewer, it can seem slow or the context confusing. And it’s a film that’s very much about a single incident, rather than a broad sweep of war or politics, so don’t expect epic, panoramic story arcs. Visually, the director Paul Katis goes for realism over spectacle. The cinematography captures the harsh Afghan landscape in a way that’s both beautiful and menacing, but never distracts from the situation on the ground. The sound design — from distant explosions to the crunch of boots near hidden mines — underscores the nerve-shredding anxiety of every movement. You would enjoy this if you’re into character-driven war stories that favor tension and realism over Hollywood heroics. It’s not flashy or romanticized, but if you want a film that feels immersive and true, with moments of grim humor and hard choices, Kajaki will stick with you.

So, Brotherhood of the Wolf isn’t your typical war film—it’s this wild French movie from 2001 that mashes up period drama, monster movie, martial arts, and political intrigue. The story is set in 18th-century France during a time of major unrest, and it follows a naturalist and his kickass Iroquois companion as they investigate the mysterious killings attributed to the legendary Beast of Gévaudan. The war aspect is more about a country on the edge, with social and political battles as much as physical ones. What stood out to me right away was the film’s stylistic boldness. Director Christophe Gans has a real flair for visual spectacle. The lush French countryside looks eerie and beautiful, and the action sequences—surprisingly acrobatic for a period piece—are creative and brisk. There’s a supernatural vibe, but also a grounded sense of historical paranoia and pre-Revolutionary dread, which keeps things interesting. The cast is eclectic and really works: Samuel Le Bihan is convincing as the passionate royal agent, and Mark Dacascos is an absolute highlight as Mani, whose martial arts scenes are so out of place that they somehow work. Vincent Cassel creeps up as a sinister, complex presence. Monica Bellucci has a mysterious, magnetic role too. Some of the French-English language mixing can be odd, but the actors are fully committed. Not everything lands, though. The plot is absolutely jam-packed, with conspiracies on top of conspiracies, and at times it feels a bit much. Occasionally the film sacrifices emotional depth for style, and some viewers might be left wanting a tighter, more focused narrative. Still, it's refreshingly weird and ambitious for a war-focused costume thriller. You would enjoy this if you like your historical war films with a supernatural twist, some martial arts, moody landscapes, and a dash of genre-bending. It’s not for purists, but if you’re open to a cultish, stylish adventure that doesn’t follow the usual rules, you’ll have a fun time.

Kajaki is one of those war movies that manages to be both incredibly tense and surprisingly restrained at the same time. It tells the true story of a group of British soldiers who become trapped in an old, unmapped minefield while stationed near the Kajaki Dam in Afghanistan. Instead of focusing on a grand narrative or action-packed set pieces, it homes in on a painfully intimate ordeal, unfolding mostly in one spot and over a single, harrowing day. What really stood out to me was how real everything felt. There’s an almost documentary style to the cinematography—lots of handheld shots, washed-out colors, and a dusty, glaring sun that makes you squint just watching it. The way the camera lingers on the soldiers as they wait for rescue makes you feel every minute tick by. You can tell the director, Paul Katis, wanted to honor the soldiers' experiences rather than glamorize them. The tension is constant. Seriously, by the end my shoulders were up to my ears. The movie isn’t about huge battles or heroic speeches—it's about small decisions, panic, and brotherhood in the face of impossible danger. The sound design (the ticking of a watch, anxious chatter, the almost oppressive silence of waiting) really adds to the feeling of being stuck with the group. It isn’t flashy, but it’s incredibly gripping. If there’s a downside, it’s that it can feel a little relentless and claustrophobic. You don't get much backstory for the characters, so it's sometimes tough to tell everyone apart at first—though that actually mirrors the confusion of the situation. Also, if you’re hoping for a break from grim realism, you won’t find it here; it’s pretty unflinching and graphic at times. You would enjoy this if you’re into war films that focus less on combat and more on the psychology and reality of soldiers in crisis. Anyone who liked the tension of movies like “127 Hours” or “The Hurt Locker” (but wants something less Hollywood) would probably appreciate what Kajaki pulls off.

Kilo Two Bravo is a British war film that recreates a harrowing true story from the war in Afghanistan. It follows a squad stationed near the Kajaki Dam in 2006, who unwittingly wander into an old Soviet minefield. The tension starts early and doesn’t really let up—there’s no big, cinematic heroics here, just an agonizingly realistic depiction of panic, survival, and brotherhood under impossible conditions. What really stood out to me was how contained the setting is; aside from a brief intro, almost the entire film takes place in this scorched, dusty, unforgiving landscape. Director Paul Katis creates a kind of claustrophobia, even though the men are technically in the open—every step is uncertain and could be fatal. The panic is raw and contagious, and the film’s use of sound and close-ups makes you feel trapped alongside the soldiers. The story doesn’t have a traditional action arc—there are no battles or shootouts. Instead, the plot is driven by a slow, mounting sense of dread as the soldiers desperately await rescue, trying to keep each other alive while working around the deadly mines. It’s more survival thriller than classic war epic, and that’s what makes it so memorable (and difficult to watch at times). Acting-wise, it’s a strong ensemble. You won’t see any huge names here, but the cast nails the accents, the inappropriate gallows humor, and the fear. No one tries to be a hero; it feels like you’re watching real people under real pressure, which only adds to the impact. The cinematography captures both the harsh beauty and the hellish danger of the Afghan terrain without feeling showy. You would enjoy this if you’re into tense, realistic war films that don’t glamorize combat. It’s heavy, sometimes upsetting, but gripping in a way that lingers for days. Definitely one for fans of true-event dramas or anyone who wants to see a side of war movies that isn’t all explosions and glory.

Set during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, "The Beast of War" (sometimes just "The Beast") is one of those war films that flies under the radar. It centers on a lost Soviet tank crew navigating hostile territory, hounded by Afghan Mujahideen, but in a refreshing switch, the Soviets are the protagonists, and the film mostly unfolds from their perspective. The isolation and tension within the tank, coupled with the unforgiving landscape, create a unique war film vibe that feels both claustrophobic and epic. What really stood out to me is how the movie mixes suspenseful thriller elements with powerful character work. George Dzundza, as the fierce tank commander, delivers a nuanced performance of a man teetering on the edge, while Stephen Baldwin (a rare dramatic role for him) plays the conflicted rookie conscript. Their shifting dynamic builds real tension, and you genuinely feel trapped with them in that metal beast. The cinematography is surprisingly beautiful given the harshness of the subject. There are wide shots of the Afghan desert that feel almost alien, adding to the constant sense that the crew is totally out of their element. The film doesn't rely on big set pieces or action sequences; instead, it builds suspense from isolation, heat, fatigue, and cultural misunderstandings, making the setting itself a character. Not everything lands perfectly—the dialogue can feel a little too on-the-nose at times, and a couple of minor characters drift toward caricature. Plus, its "message" moments are sometimes heavy-handed. Still, the uniqueness of its point of view (not to mention its solid, practical effects) make up for most of the rough edges. You would enjoy this if you liked "Das Boot" or "Lebanon," or you just want a war film that isn't all about big battles and American soldiers. It's an underrated, tense, and thought-provoking look at how war can turn almost anyone into prey and predator at the same time.

Defiance tells the true story of the Bielski brothers, who rescued and sheltered Jewish refugees during World War II by forming a forest community in Nazi-occupied Belarus. What stands out most is the grounded portrayal of survival — not just in the face of violence, but through the emotional tension of keeping a fragile society together in hiding. While it’s well-known among war movie fans, it doesn’t come up nearly as often as other WWII films, which is a bit of a shame. Daniel Craig leads the cast with sturdy conviction, trading James Bond’s gadgets for desperation and grit. Liev Schreiber shares the screen, bringing a rugged and passionate counterpoint. There’s real chemistry and tension between the brothers as they face impossible choices, and the supporting cast does a solid job flushing out the community’s hopes and heartbreak. The narrative sometimes feels a little unfocused, though — it wants to balance action, drama, and romance, and occasionally bites off a bit more than it can chew. What I especially liked was the wintry cinematography. The bleak, snowy forests look beautiful but also isolating and forbidding, mirroring the group’s struggle against not just Nazis, but nature itself. There’s a sense of claustrophobia and unease that really pulls you into their world. The sound design is another high point—gunfire and shouts echo through the trees, making moments of peace and safety feel fragile. I will say, the pacing can drag in the middle, especially as the film tries to juggle individual character arcs with the broader survival story. Some relationships and motivations aren’t explored quite as deeply as they could be. Still, the emotional weight lands, especially in the final act when survival turns into resistance. You would enjoy this if quiet, human-focused war stories appeal to you—especially ones grounded in lesser-known true events. It’s not as bombastic or action-heavy as other WWII movies, so if you like your war films with a dose of moral ambiguity and a strong sense of place, give Defiance a shot.

Kajaki is a British war film based on a true story, and it's one of those movies that grabs you with its grounded sense of terror rather than non-stop action. The story follows a squad of British soldiers stationed near the Kajaki Dam in Afghanistan in 2006, and what starts as a normal day unravels into chaos after one of them steps on an old Soviet landmine. Instead of shifting to firefights and explosions, most of the film operates on gut-wrenching tension as the men try to survive and help each other while surrounded by hidden mines—it's more about fear and camaraderie under the harshest circumstances. What really stood out for me was how contained and claustrophobic everything feels, even though they're technically out in the open. The camera work is raw and almost documentary-like, keeping you in the thick of the action (or lack thereof). This isn't a patriotic, flag-waving war film; it's a gripping portrayal of the randomness and brutality of war, and the way small decisions can have massive, irreversible consequences. The acting is strong across the board, and although you might not recognize the actors, that unfamiliarity actually makes their performances feel all the more authentic. There's a lot of ensemble work here, with subtle moments of panic, dark humor, and desperate resourcefulness. No one character outshines the rest, reflecting the actual teamwork (and shared terror) that happens in situations like this. If anything didn't quite land, it's that the tight focus on a single incident and its aftermath can make the film feel a bit repetitive or emotionally numbing as you watch the men wait for rescue. The tension rarely lets up, and if you're hoping for character backstories or a look at the wider war, this isn't that movie. Still, it's for the most part a deliberate choice—the monotony and dread are what make the horror of the situation hit so hard. You would enjoy this if you like your war films stripped of Hollywood gloss, or if you're interested in the psychological struggles rather than epic set pieces. It's definitely for people who can handle nerve-jangling suspense and don't mind a slow-burn, merciless pace. I wouldn’t call it “enjoyable” in the traditional sense, but it’s gripping, human, and will leave you thinking afterward.

The Painted Bird is a haunting, unsettling war drama that I stumbled across a while ago, and it hasn’t quite left my mind since. It’s a Czech film based on Jerzy Kosiński’s controversial novel, focusing on a young boy wandering through Eastern Europe during WWII. With dialogue kept sparse and the little protagonist mostly an observer, it’s almost a silent odyssey through some of the most harrowing corners of humanity. You’re not really watching the war itself but its ripples and devastation on smaller, faraway villages. What really stands out is the film’s stark black-and-white cinematography. Every shot feels meticulously composed—a chillingly beautiful contrast to the brutality onscreen. There are landscapes you could almost hang on a wall, if not for the violence that keeps you at arm’s length. The film doesn’t flinch when depicting cruelty, and I’d honestly recommend looking up content warnings before diving in. The storyline itself is episodic, almost picaresque: the boy drifts from one traumatic encounter to another. Sometimes it feels almost overwhelming—there’s a sense of desensitization as things get bleaker with every chapter. It can lull you into numbness, which I think is partially the point, but it occasionally makes the experience feel punishing more than illuminating. The performances are strong without being showy; Petr Kotlár, the young lead, barely says a word yet communicates so much pain and confusion. There’s a parade of international actors in supporting roles too (including Stellan Skarsgård and Harvey Keitel), though their appearances are often brief and their characters unapologetically cold. What struck me was how the film resists giving you someone easily likable to root for—it wants you to grapple with the ugliness. You would enjoy this if you’ve got patience for slow, intense art-house cinema and want something very different from the typical action-packed war movie. If you’re interested in seeing the psychological impact of war on individuals, especially children, and you don’t mind bleak, sometimes shocking content, The Painted Bird is powerful. But it’s definitely not light viewing.

I caught "The Siege of Jadotville" on a recommendation, and it's one of those war movies that feels a bit off the beaten path. The story covers a lesser-known episode from the Congo Crisis in 1961, centering around a group of Irish UN peacekeepers who find themselves vastly outnumbered and under siege. What caught my attention right away is that it isn’t your typical, explosive “hero’s journey” war film—there’s a real sense of ordinary men thrown into extraordinary circumstances. Jamie Dornan surprised me as the quiet but resolute Commandant Pat Quinlan. He brings a calm, understated charisma to his role that carries the movie, even when some of the other performances are a bit flat. The film does a good job conveying the camaraderie among the men, and you genuinely feel the tension and fear as the odds stack up against them. The slower pace at the start pays off when the action finally kicks in—every bullet feels consequential. Cinematography-wise, the movie punches above its weight. The African landscape serves as a fierce, beautiful backdrop, and the siege scenes are shot with a gritty, unglamorous realism. The washed-out color palette fits the period and mood perfectly. You really sense the heat, exhaustion, and claustrophobia, especially as supplies dwindle and hope fades. If the film struggles anywhere, it’s in fleshing out the political complexities of the conflict. It touches on UN bureaucracy and the murky motivations behind the mission, but some of that gets sidelined for more immediate action. Secondary characters could have used a bit more depth as well; at times they blur together beyond a few memorable faces and one-liners. You would enjoy this if you like intelligent, tense war stories that focus more on endurance and leadership under pressure than on gory spectacle or big-budget effects. It’s a rewarding watch for those interested in historical conflicts that don’t always make the history books or for folks who appreciate a more grounded, character-driven approach to the genre.

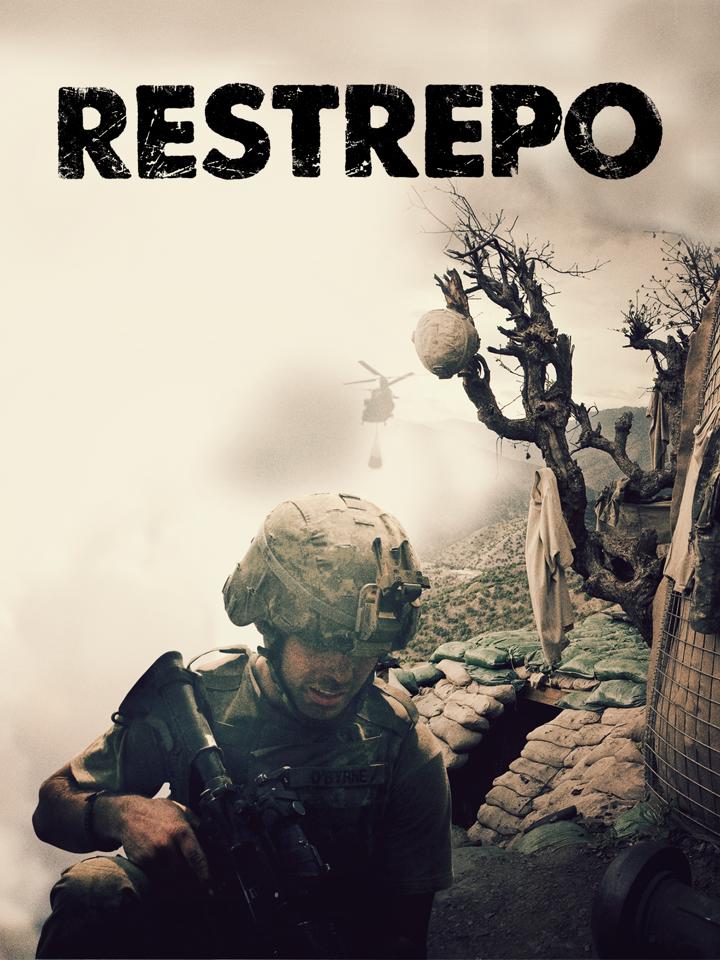

Restrepo is one of those war documentaries that sticks with you long after the credits roll. Directed by Sebastian Junger and Tim Hetherington, it drops you right into Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley alongside a platoon of U.S. soldiers in 2007-2008. The setup is as minimal as it gets: no voiceover, no talking heads, just raw handheld footage, shaky and immediate, with everything unfolding in real time. If you’re used to Hollywood’s glossy polish, this one will feel like a bucket of ice straight to the face. The thing that grabbed me most is the sense of claustrophobia. The entire film is set at Outpost Restrepo, a barely fortified hilltop no one in their right mind would volunteer to defend. The camera work is frantic but never showy, and you get winded just from watching the soldiers run through trenches or scramble during firefights. Sometimes you’re waiting hours, sometimes nothing happens at all. That grind, that constant low-level anxiety, feels absolutely true to what I imagine combat might be. As for the guys themselves, the film gets painfully close to them. You meet these young soldiers, see their bravado, their jokes, their stupid inside gags. Then you see them devastated, losing friends, and the cracks in their armor start to show. There’s a scene where one soldier talks about his dog back home; it’s not a big moment but it cuts deep, because you realize how young and out of their depth most of these guys are. The directors don’t need to spell anything out. The emotion is baked into every shaky frame. What didn’t work so well for me? Sometimes, the “fly on the wall” approach gets almost too in-your-face. There’s not a lot of context for why these men are there or why this particular outpost matters so much. If you’re not familiar with the broader Afghanistan conflict already, you’re going to feel a little lost. On the other hand, maybe that’s the point: out on those hills, everything beyond the next moment seems abstract and far away. But still, a bit more narrative context might have given some sequences more punch. The pacing is a slow burn, and I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel restless in a few stretches. Unlike a traditional war film, there’s no triumphant arc, no sense of a clean story structure or “big mission” payoff. The tension ratchets up then fizzles out, just like it probably did for the soldiers themselves. This can feel frustrating, but by the end, I appreciated the honesty of it. Restrepo isn’t trying to entertain you; it wants you to sit in the mess of real war. Tonally, the movie is bleak but never hopeless. The soldiers’ dark humor and camaraderie provides bursts of relief, but the overall vibe is heavy. There’s a tragic cycle to everything they do. One moment they’re celebrating, the next they’re grieving, and it just keeps going in loops. If you’re looking for a cathartic release or a hopeful message, look elsewhere. This film is about the wear and tear on real people, not about winning or losing. Cinematography deserves its own mention. Even though it’s “just” documentary footage, every shot feels loaded. The landscapes are both beautiful and hostile, the camera often catching little moments—mud on boots, nervous hands gripping rifles, silent faces staring into space. The auditory landscape is chaotic: sudden gunfire, the rustle of sandbags, the buzzing of flies. You can practically smell the sweat and fear. At the end of the day, Restrepo is war stripped bare. No dramatic soundtrack, no grandstanding politicians, just humans surviving day by day, doing a job that sometimes seems pointless even to them. It’s not perfect, and sometimes it’s overwhelming or confusing, but it’s one of the most honest war films I’ve ever seen. If you’re the type who wants answers or resolution, you’re not going to find it here. But if you want an unfiltered glimpse into modern combat, Restrepo is worth the watch.

The first thing you notice about 1917 is the pace. This film is relentless. Sam Mendes dials up the tension immediately and never really lets it drop. The premise is set within the first ten minutes: two young British privates have to cross enemy territory to deliver a message that could save 1,600 lives. It’s simple, brutal, and claustrophobic from the start. The film’s “one-shot” illusion is everywhere, making you forget there’s a camera at all. I’d never seen a war film that feels this immediate—like a panic attack that doesn’t quite fade until the credits roll. George MacKay deserves a lot more attention for what he does here. His face spends most of the movie absolutely drained, with real fear and exhaustion showing up even before things get truly bad. There are long stretches where he’s the only person on screen, and the movie trusts you to follow him without any dramatic speeches or forced character development. This is a war movie that doesn’t want to glorify anything. Instead, it commits to showing how draining and impersonal the experience feels. It’s hard not to talk about Roger Deakins when discussing 1917. Deakins is a beast behind the camera, and he’s sort of the real star of the movie. The cinematography is on another level: muddy trenches, bombed-out ruins, night flares painting everything in surreal shades, and these breathtaking open fields that somehow feel terrifying and beautiful at the same time. There’s a sequence when the characters cross a ravaged French town at night that stands out as one of the most visually stunning moments I’ve ever seen in a war film—harrowing, dreamlike, and unforgettable. But if I’m being picky, the one-take shtick can sometimes get distracting. Instead of sinking deeper into the story, you catch yourself thinking, “How did they do that?” I admire the technical prowess, but sometimes it undercuts the emotional beats. There are moments where the film’s need to maintain the illusion overrides character choices. For example, the conversations can feel basic, almost like the game dialogue you hear in a first-person video game. It made me wish they trusted the performances to stand on their own more, rather than relying on spectacle. The film’s tone is dead serious, carrying this weight of dread from start to finish. There isn’t much humor or camaraderie: war is hell, and Mendes wants you to sit with that discomfort for two straight hours. There’s a certain bleak honesty to it, but it also means the emotional highs don’t land as hard. When something tragic happens, you’re expected to be moved by sheer momentum rather than a full understanding of the characters’ inner lives. Even the brief backstory bits feel half-hearted, almost perfunctory. To be fair, that’s probably the point. You never really get to know these soldiers. The whole movie is about disconnection: from home, from humanity, even from themselves. You follow the mission, not the man. That focus keeps the film moving at a breakneck clip, but it can leave you feeling strangely numb by the end. The few gut-punch moments that do land are more about the horror of the situation than any specific attachment to the characters. Where 1917 really comes alive is in its sense of place. The production design is meticulously grimy—trenches, collapsed farmhouses, and rivers littered with the debris of failed attacks. You don’t just see World War I, you smell it, which is just about the highest compliment I can give. The attention to detail makes the film a sensory punch in the gut, and the suspense comes as much from anticipation of what’s around the next twist in a maze of misery as it does from overt action. I walked away from 1917 feeling impressed, but also a bit exhausted. It’s a technical marvel and one of the most immersive depictions of trench warfare ever put on screen. If you want intimacy, character arcs, or big philosophical statements, you’ll probably be left wanting. But if you want to be right there on the ground, flinching at every gunshot like a shell-shocked extra, this movie nails it. It stays with you—cold, muddy, and a little bit broken.

When I first saw Fury, I wasn't expecting something completely out of the box, but I did want a little grit and realism. The film, directed by David Ayer, absolutely delivers on the down-and-dirty front. Set during the last days of World War II, it follows a ragtag crew of American soldiers crammed into a Sherman tank, rolling across war-torn Germany. Brad Pitt is their steely commander, nicknamed "Wardaddy," and honestly, his performance is intense, stubborn, and way dirtier than most leading-man roles. From the very first scene, Fury makes it clear this isn’t your uncle’s war movie. The world is muddy, chaotic, and brutal, and the script doesn’t shy away from ugly truths about violence or the futility of war. The tank itself becomes a claustrophobic, almost hellish home to the crew, and Ayer's camera work makes sure we feel every shudder, every loud clang, and every single spray of mud or blood. There’s a craftsmanship here, especially with sound design, that’s hard not to appreciate—even when the movie meanders a little or leans into the melodrama. The cast really does most of the heavy lifting. Logan Lerman plays the newbie, Norman, whose shell-shocked introduction to war gives the audience a kind of stand-in. His arc is clear, maybe a little too predictable, but it’s honest. Jon Bernthal is reliably rowdy as Grady, and Michael Peña’s steady presence really grounds the group. Shia LaBeouf’s performance stood out as Bible, the gunner, who is drawn with quiet sadness and a weird, offbeat sincerity. These guys manage to feel like they’ve been fighting and suffering together much longer than their screen time would suggest. That being said, Fury sometimes tries a bit too hard to dig at your nerves. There’s one scene in particular set inside a German apartment that absolutely drags—Ayer sets up a temporary peace, but the tension never quite pays off in emotion. It feels manipulative instead of meaningful, and it’s one of the film’s low points for me. It's a moment that wants to say something profound about humanity, but it's just too on-the-nose and overlong. Cinematography is a highlight, though. There’s a striking bleakness in every frame, with muted colors and brutal battlefields that make you feel the mud in your teeth. Some of the wider shots of the tank creeping through fog or fire look painted rather than filmed. But Ayer never lets the stylization overshadow the grime—this is a filthy, confined war, not some epic saga. The action scenes are loud and punishing, which fits the overall tone. You can tell the film did its homework on tank warfare. There are moments where you feel genuinely trapped and panicked alongside the crew. The sound of ricocheting shells and the slow, grinding movement of the Sherman tank force you to reckon with just how miserable and terrifying armored warfare must have been. Tonally, Fury doesn’t have much in the way of hope. It’s more about survival, about what these men are willing to do (or sacrifice) as the war grinds on. It’s honestly a little exhausting at times, and I think that’s the point. The pacing is solid enough for most of the film, but it does stall near the middle, with some character beats that feel less earned and more inserted for effect. Not every emotional note lands—sometimes it’s more yell than melody. Does Fury reinvent the war movie? Not really. But it does offer a raw, dirty, and mostly un-romanticized look at combat. The film’s heart is in its performances and its commitment to misery, and when it leans into those strengths, it hits hard. If you're in the mood for something bleak, noisy, and full of dirt-under-the-nails realism, it’s a worthwhile watch. Just don’t expect to walk out whistling a happy tune.