Browse our collection of western reviews and ratings.Showing 12 of 16 reviews.

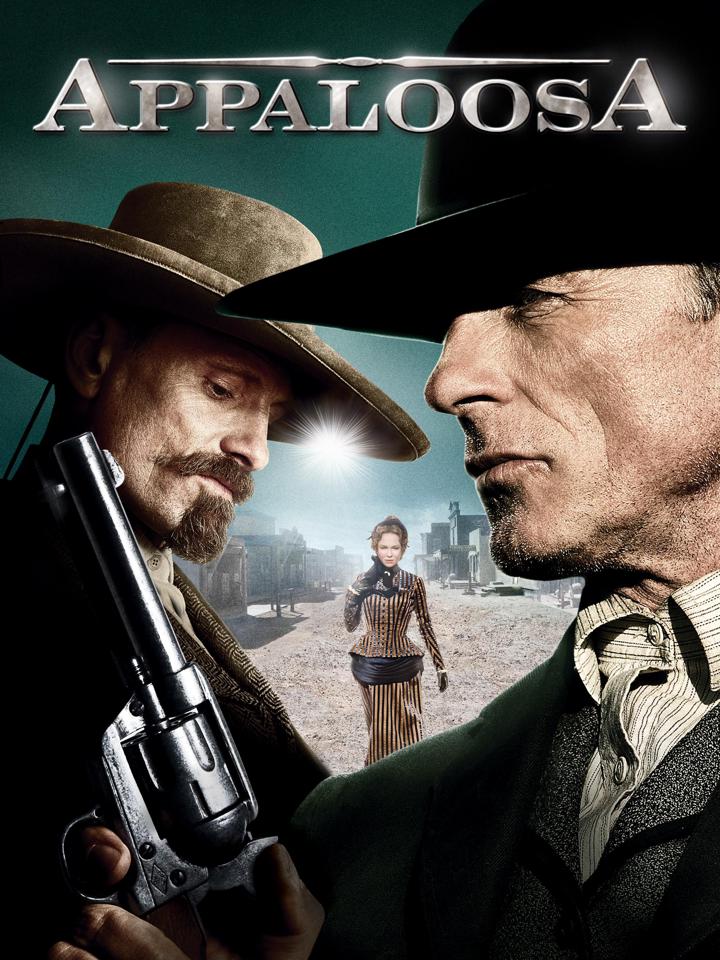

Appaloosa is one of those Westerns that sneaks up on you with its dry wit and strong character work. It’s about two itinerant lawmen, played by Ed Harris and Viggo Mortensen, who ride into a troubled New Mexico town hired to bring order against a ruthless rancher, played by Jeremy Irons. The movie hums along at a steady, unhurried pace, focusing less on shootouts and more on the relationships between the characters—which feels really refreshing if you’re a little burnt out on the typical action-heavy Westerns. What really drew me in was the dynamic between Harris and Mortensen’s characters, Virgil Cole and Everett Hitch. Their friendship is understated but feels genuinely lived-in, and watching them navigate moral gray areas together is easily the highlight. The dialogue is sharp without being showy, and there’s a kind of gruff humor that seeps through the dusty landscape. Renée Zellweger comes in as a complicated love interest, though her storyline doesn’t have quite the depth I wanted. The pacing is slower than most big-name Westerns, and it probably won’t work for anyone looking for a constant barrage of gunfights. Some of the story beats—especially around the romantic subplot—feel a bit forced, and I never entirely bought into Zellweger’s character or her motivations. Still, the film wisely keeps its focus on the central friendship. Cinematography-wise, Appaloosa isn’t showy, but it makes the most of its desert settings. The visuals are less about grand, sweeping vistas and more about quiet town streets and the tension simmering under the surface. It feels intimate in a way, which really matches the more character-driven storyline. You would enjoy this if you’re into Westerns that are more about atmosphere and characters than spectacle, or if you liked 3:10 to Yuma but want something a little quieter and more off the beaten path. It’s a low-key gem for anyone who appreciates a good, old-fashioned partnership at the heart of their Western stories.

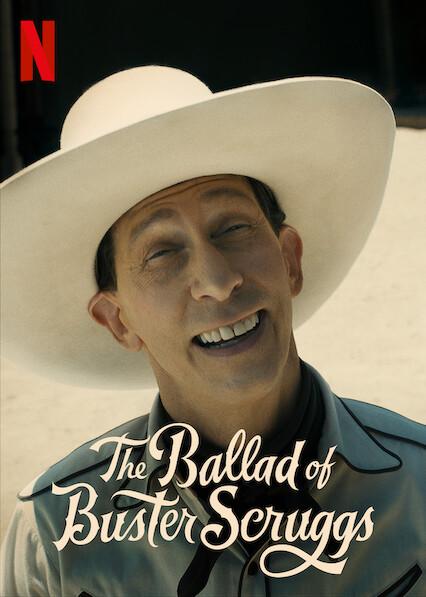

This Coen Brothers anthology film is a wild take on the Western, offering six distinct tales set on the open frontier. Each story is unique—some are darkly comedic, others melancholy or downright tragic. The framing is clever: the film presents itself as a dusty old storybook, its yellowed pages flipping between vignettes about outlaws, gold prospectors, or vaudeville performers down on their luck. That first segment with Tim Blake Nelson’s singing gunslinger? It’s hilarious in a totally unexpected way. What stood out for me the most was the sheer variety in tone and pacing. No two stories feel the same, yet they’re all stitched together with that signature Coen Brothers wit and sense of irony. A couple of the segments, like Tom Waits’s gold digger or Liam Neeson’s tragic stagecoach act, really lingered with me after the credits rolled. The script is full of tiny details—turns of phrase, character quirks—that add depth beyond the typical shootouts and saloons. Not every story is equally strong. One of them (without spoiling which) felt a bit like filler; it dragged compared to the others and didn’t stick the landing for me. The overall structure takes you in many directions, sometimes abruptly, which is fun but can make it hard to settle into the movie’s rhythm if you’re expecting a single plotline or central hero to root for. Cinematography here is gorgeous—bold desert vistas, snowscapes, candlelit interiors—shot with a vintage gloss that makes each storybook panel pop. The performances are spot on, with character actors and famous faces alike bringing real zest (and, often, pathos) to their brief time onscreen. The visual style feels playful but reverent, and there’s a musicality to the pacing, aided by Carter Burwell’s evocative score. You would enjoy this if you like Westerns but want something that comments on the genre with a wink, rather than just replaying familiar tropes. It’s great for fans of dark humor, quirky storytelling, and anyone who doesn’t mind a movie that changes gears often. If you liked Fargo or O Brother, Where Art Thou?, this should be right up your alley.

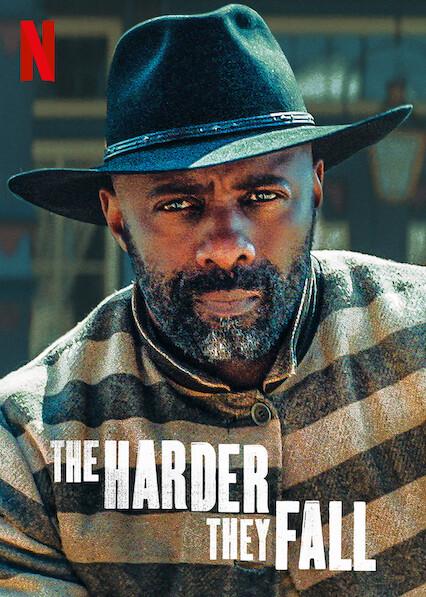

This one's a Western but with a fresh and considerably stylish twist — an all-Black main cast, a soulful soundtrack, and a pulpy sense of fun throughout. "The Harder They Fall" takes the classic good guy-outlaw rivalry and injects a ton of charisma into it, pitting Jonathan Majors and Idris Elba against each other with a supporting cast that's just as magnetic (Regina King is a highlight, as usual). The setting is rooted in the tropes we all know — dusty towns, saloon fights, train heists — but it always feels like it's having genuine fun playing with the genre. What stood out most for me was the sheer energy. Director Jeymes Samuel has a knack for sleek visuals and kinetic pacing, making gunfights feel like music videos without getting too MTV. The movie is visually stunning, from the sandblasted landscapes to the bold color pops in costumes and set design. The moments between gunfights allow the cast to actually build out their characters, which is more than you get in a lot of modern action-westerns. Admittedly, the movie sometimes leans a little too hard into style over substance. Some of the emotional beats felt a tad thin, and there’s a lot going on — perhaps too much for its runtime. If you're hoping for a super deep character study or a slow-burn mood piece, you might be a bit disappointed. But as an energetic, modern Western that doesn't shy away from having fun, it delivers. It's also worth mentioning how much the film embraces its influences while staying authentic to its own identity. You can feel the echoes of Tarantino and Sergio Leone, but it never feels like a mere imitation. The soundtrack, which mixes hip-hop, reggae, and classic Western cues, really sets it apart, and there's a clear love for the genre and its history throughout. You would enjoy this if you want a Western that's visually bold, moves fast, and brings some fresh faces and perspectives to the genre. If high style, great music, and classic showdowns sound appealing, this is a fun watch to add to your list.

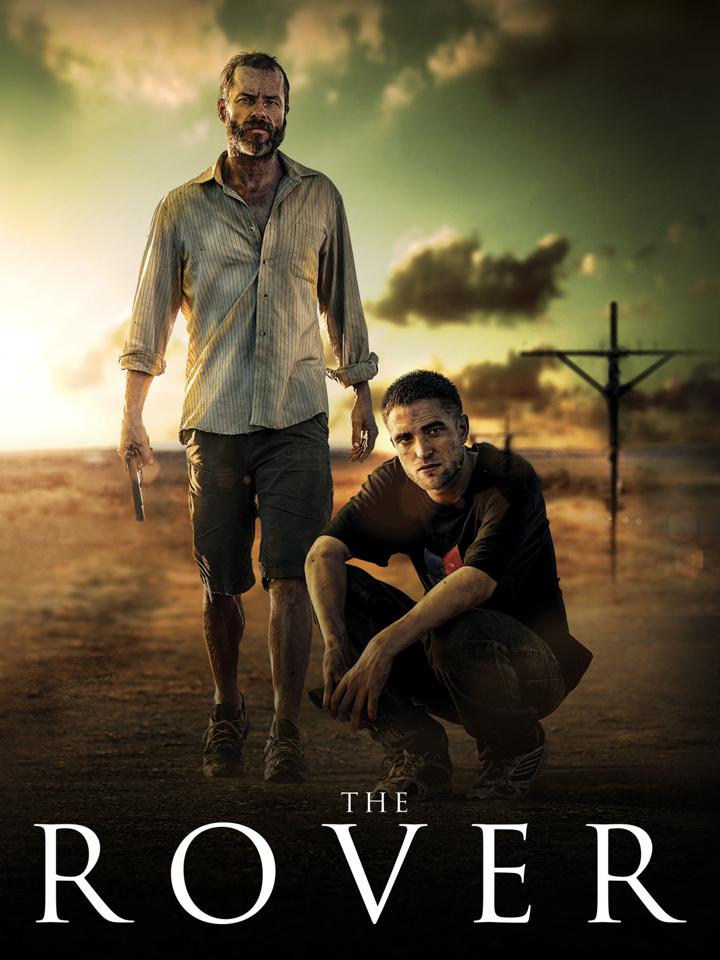

So, "The Rover" is an Australian post-apocalyptic western from 2014, and I feel like it really slipped under the radar for a lot of people. Set ten years after a global collapse, it's a bleak, slow-burn road movie that feels like a spiritual cousin to "Mad Max" but more stripped down and gritty. The story follows a drifter (Guy Pearce) chasing down the gang who stole his car, with an unhinged younger brother (Robert Pattinson) in tow. It’s not your usual action-packed Western—this one is all atmosphere and tension. What really stood out to me was the setting. The Australian outback is almost a character itself—harsh, barren, and eerily beautiful at times. The cinematography makes you feel the heat and emptiness, and there's this constant sense of danger lurking behind every scrub bush. The movie moves at its own, deliberate pace, which makes the few bursts of violence feel all the more shocking. Guy Pearce as the lead is quiet, intense, and honestly pretty terrifying. He barely says a word but you can read so much in the way he moves and looks at people. Robert Pattinson was a surprise for me too—his role is jittery, vulnerable, and strangely moving. Their uneasy partnership gives the story some emotional stakes and you end up caring about what happens to them, even if they're not exactly likable. I will say, the slow pace might not be for everyone. If you want shootouts and big hero moments, this won't scratch that itch. The story keeps things ambiguous and not all your questions get answered, which can be frustrating, but in a way that feels true to the grim world the film builds. The atmosphere wins over conventional Western plot beats here. You would enjoy this if you like your Westerns bleak and introspective, or if post-apocalyptic stories with shades of grey appeal to you. It has that atmospheric, almost hypnotic vibe like "The Proposition" or "No Country for Old Men" (but more indie). It's a tough, haunting watch—but it sticks with you.

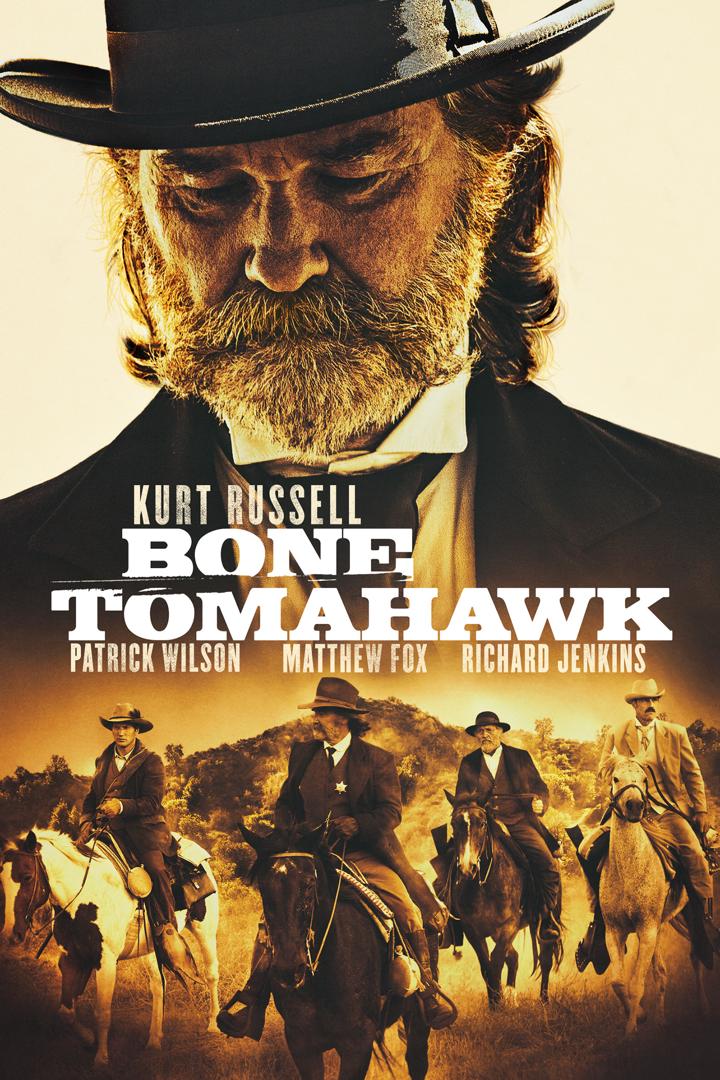

You know how sometimes you pick a movie just to have something on in the background, and then you end up glued to the screen? That was my experience with Bone Tomahawk. On paper, it sounds like a pretty simple Western: a small-town sheriff sets out with a ragtag posse to rescue some kidnapped townsfolk. But what you get is this slow-burn, genre-mashing fever dream that manages to be both a loving homage to classic Westerns and a total gut-punch of horror. Kurt Russell is the heart and mustache of this film, playing Sheriff Hunt with that laid-back authority he brings to pretty much everything. He doesn't chew the scenery or ham things up, which works because the movie itself is so restrained most of the time. The rest of the group—Richard Jenkins, Patrick Wilson, and Matthew Fox—each offer something distinct. Jenkins especially is almost unrecognizable as the aging deputy, bringing this gentle, forgetful warmth to the role that makes some of the grim moments hit harder. The first hour is noticeably patient. Some people might call it slow, but for me it was more like simmering tension. S. Craig Zahler lets the characters breathe and talk like real people instead of plot devices. There are scenes where guys just sit around a campfire, bickering about the meaning of words or swapping old war stories. It gives the journey some weight because you actually believe in these tired, flawed men, not just the mission they're on. Cinematography stands out in a really stripped-down way. There's nothing flashy going on, which feels true to the setting. Wide desert shots, dying campfires, dust motes catching the morning light—that sort of thing. The movie leans into the gritty reality without trying to look too pretty or stylized. It reminded me of some of John Ford’s classic Western landscapes, but with this focus on rawness rather than grandeur. I have to talk about the tone shift, because Bone Tomahawk is notorious for it. For almost ninety minutes, it's a moody but straightforward Western. Then out of nowhere, it takes a hard detour into pure horror. When it happens, it’s shocking and honestly a little nauseating. There’s one scene in particular that goes so far it’s almost cruel, and I’m still surprised I didn’t look away. That might sound like a criticism, but the violence here isn’t done cheaply—it’s earned by the slow build and the desperation the characters are feeling. That said, I’m not sure everyone will appreciate how brutal things get in the last act. Zahler doesn’t pull his punches, and if you’re squeamish about gore, this is a rough watch. But honestly, the cruelty is the point. The film wants to unsettle you, to make you question the myth of the frontier hero in a place where the wilderness is actually terrifying. It’s bold, but not exactly fun. Story-wise, some people will find the setup a little thin. The central quest is basic: ride out, rescue the captives, bring 'em home. What keeps it engaging isn’t so much the what, but the how—every pit stop reveals something new about the characters, their simmering prejudices, regrets, and hopes. The payoff is that it makes the outcomes, good or bad, stick with you long after the credits roll. For me, Bone Tomahawk hits this rare spot between throwback Western and unflinching horror. I have some gripes about the pacing—certain scenes feel like they linger just a bit too long, and the ending could have trimmed a couple minutes. But man, if you’re looking for something that sticks in your teeth and doesn’t let go, this one is it. Just don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Let’s talk about Hell or High Water, a 2016 neo-Western that’s as much about broken families and failed systems as it is about bank robberies. The setup is deceptively simple: two brothers, played by Chris Pine and Ben Foster, decide to rob a string of Texas banks. On the surface, it’s a modern Western with dusty roads and sunburnt horizons. But right when you expect it to go full action, it slows everything down, leaning into a deeper reflection on poverty, legacy, and desperation in middle America. Taylor Sheridan’s script pushes this beyond the usual genre trappings and lets you sit with characters who are lost but determined. One of the things that hit me right away was the tone. There’s a weary humor in the dialogue and a sense of resignation cloaked in bravado. Jeff Bridges plays Marcus, the old Texas Ranger on their trail, and he brings exactly the sort of crusty charm you’d hope for. The banter between him and his partner is sharp but never showy, layered with affection and sadness, especially as Marcus faces down the end of his own career. It’s a different vibe from something like No Country For Old Men, but still feels steeped in a sort of cinematic melancholy. Visually, it’s spot-on. Director David Mackenzie and cinematographer Giles Nuttgens shoot Texas in a way that’s both romantic and brutally honest. You see the rust, the abandoned lots, the faded storefronts—this isn’t a glossy Marlboro Man fantasy. There’s a haunting sense of place that’s less about nostalgia and more about how communities are left behind. It’s beautiful and bleak at the same time. The way the camera lingers on details, like sweat on a brow or the quiet stillness of a flat landscape, adds a ton of atmosphere without ever feeling overindulgent. Pacing-wise, Hell or High Water takes its time but never drags. It’s not rushing toward big, explosive shootouts, though there are moments of very real violence. The tension builds and releases in unexpected spurts. I never found myself bored, but there are stretches that are just two characters talking in a car or staking out a bank. Those slow moments actually have a cumulative weight. That said, if you’re looking for rapid-fire action, this movie simmers more than it boils. The acting is honestly top-tier. Ben Foster, as the wilder, damaged brother, walks this razor line between reckless and quietly tragic. Chris Pine plays against his usual pretty-boy type and nails the understated, world-weary core of his character. Their relationship feels lived in—you believe these guys are siblings with a history of heartache and rough choices. Even the supporting cast, like the snarky waitress or the racist old man in a bank, make these little corners of Texas feel specific and real. If I had to nitpick, I think the movie’s attempts at social commentary sometimes get a bit on the nose. There’s some pointed dialogue about foreclosure, predatory loans, and the death of the working class that’s important but at times feels too spelled out. I’d argue the visuals and character studies get the point across more effectively than some of the speechifying. It’s not enough to derail the film, but there were maybe two or three moments where I thought, “Okay, I get it, let’s move on.” The emotional weight is what surprised me most. Beneath the crime plot and cat-and-mouse setups, this is a story about love and survival—family obligations that feel like a burden nobody asked for but can’t escape. There are no clear heroes, and the line between good and bad is drawn so faintly you might miss it. The ending hangs heavy without needing a speech or summing up. It kept me thinking about what justice and redemption actually mean for people who have run out of options. All in all, Hell or High Water is a Western that feels right for now: a sharp, soulful piece that hits with both style and substance. It’s not a perfect movie, but its imperfections are mostly endearing and human. If you’re tired of shiny blockbusters or stale genre retreads, it’s a breath of hot, dusty air. I’d say it’s the kind of film that’s even richer on a rewatch, where the quiet moments reveal just as much as the shootouts.

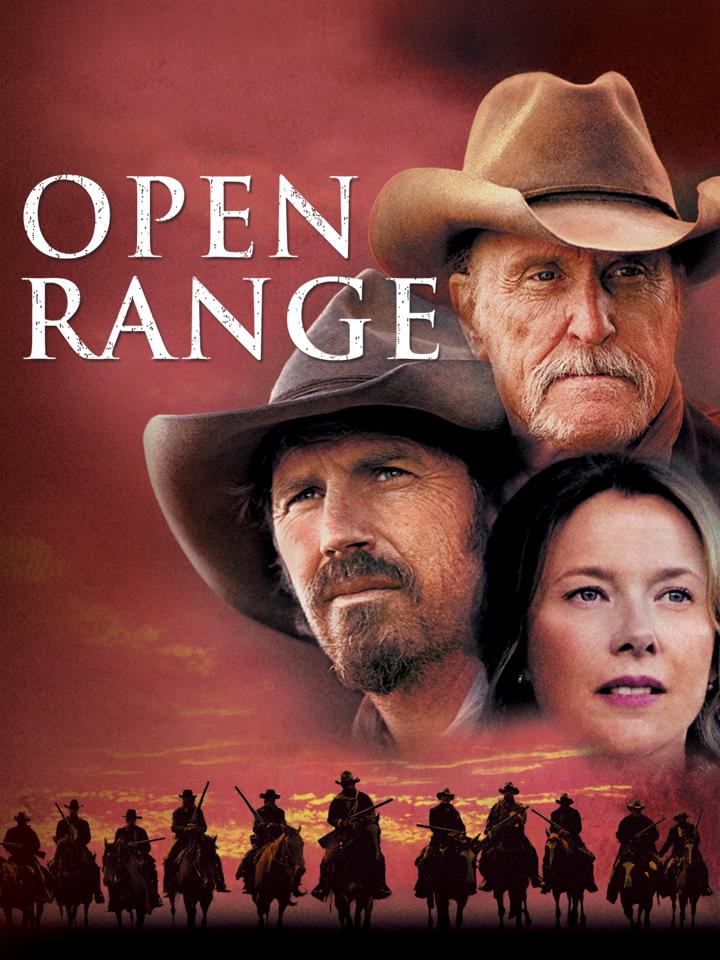

Open Range is one of those Westerns that flew under a lot of people’s radar, even though it stars Kevin Costner and Robert Duvall. Released in 2003, it has that comfortable period authenticity that Costner likes—weather-beaten faces, dirt under the fingernails, and a slow, rolling pace. The setup is simple: two free-grazers and their small crew get bullied by a powerful rancher in a town that isn’t exactly friendly to outsiders. It's not flashy, but there’s something really steady and almost meditative at work here. The first thing that stood out to me was the chemistry between Costner and Duvall. Duvall’s character, Boss Spearman, has a relaxed, unhurried way of owning every scene. Costner plays Charley Waite, a former gunslinger nursing old wounds, both physical and emotional. Their partnership feels real. There’s a father and son dynamic that gives the film some warmth, even as it teeters toward violence. When they share quiet moments between chores or by the fire, you feel the history. The pacing is definitely on the slower side. Some might call it patient, others might say it drags, but you can tell Costner is channeling those grand, deliberate epics. He isn’t rushing to the next shootout. Instead, the tension simmers for a long time. The movie really makes you wait before anything explodes, which can be both a strength and a weakness. I caught myself wishing they’d hurry up at times, but looking back, the buildup gave weight to the final act. Cinematography here is superb. Everything feels wide open, windswept, and honest. Fields stretch into the horizon, and every shot seems to find a quiet dignity in the land itself. Costner lingers on these big, empty spaces, which gives the movie both a sense of freedom and isolation. There’s one particular scene—in the rain—that perfectly captures the mood of the film: melancholy, with a touch of foreboding. Every now and then, the sky and the grass become characters in their own right. The violence, when it comes, is shockingly quick and brutal. No slow-motion, no stylized blood sprays. Just loud, awkward, messy gunfights that feel closer to what guns actually do. The final shootout feels like it punches you in the chest—no melodrama or celebration, just chaos and survival. That kind of realism is hard to pull off and it really worked for me. When people die in Open Range, the film doesn’t look away or romanticize it. Of course, the movie isn’t perfect. Annette Bening’s character, who provides the main romantic subplot, sometimes feels underwritten. Her motivations never fully click, and her chemistry with Costner lands somewhere between “neighbors who chat” and “let’s get this over with.” The script wants her to be pivotal, but she’s mostly there to move Costner’s character along and soften the edges, which is a missed opportunity. What I appreciated, though, is the restraint. So many Westerns dip into caricature—the black-hat villain, the saintly townsfolk, the tortured hero. Open Range keeps things pretty grounded. Even the main antagonist, played by Michael Gambon, isn’t just evil for evil’s sake. He’s a controlling, petty man, yes, but he’s believable. The town feels lived-in, with people who are scared and self-interested. It’s a Western that cares more about small gestures than grand speeches. By the end, I felt like Open Range earned its emotions. You get to know these characters and care about them, not because of flashy plotting but because the film lets them be vulnerable and ordinary. If you have patience for a slow-burn Western with an old-fashioned heart, you’ll find plenty to love. It’s not quite Unforgiven, but it’s got grit and grace in equal measure.

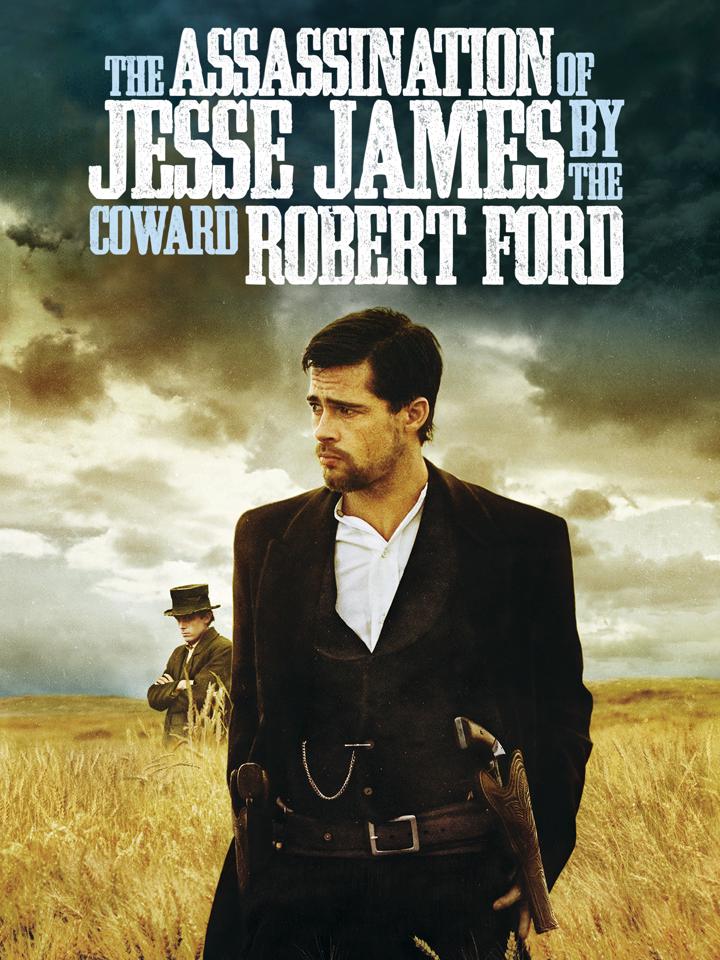

Alright, let’s get into it. "The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford" (what a title) is one of those Westerns that makes you feel like you’re inhaling old paper and dust, like flipping through some relic novel you found in your grandpa’s attic. It’s long, slow, and soaked in mood — the antithesis of popcorn action. I rewatched it recently, and it still feels as haunting and oddly graceful as it did the first time around. The story, in its bones, is pretty direct: It’s about Robert Ford’s obsession with Jesse James, the most notorious outlaw of his day, and the legendary betrayal that followed. But there’s little in the way of classic gunfights or barroom brawls. Instead, it’s like a psychological slow-burn where every character feels a touch off-kilter. The tension builds in quiet stares and half-muttered lines, not wild shootouts. The real secret ingredient is the cast. Casey Affleck puts in a performance so awkward it’s almost painful to watch — but in exactly the right way. His Robert Ford is needy and insecure, desperate for relevance, and you can practically see the flop sweat. Brad Pitt, meanwhile, seems to understand Jesse James as both folk hero and fraying man, more melancholy than menacing most of the time. And when these two share the screen, everything else goes fuzzy around the edges. There’s a weird chemistry there: admiration sparring with jealousy, friendship tangled with fear. Roger Deakins’ cinematography deserves a whole paragraph of its own. Some shots somehow manage to look both grimy and poetic at once. There are those dreamlike train scenes dusted with fog, the pale winter grass stretching endlessly, and houses swallowed by dusk. Even if you zone out on the plot, the visuals could hypnotize you into sitting through the two and a half hours. But okay, here’s where it splits the crowd: the pacing. This thing moves at the speed of molasses. I mean, you could go make a coffee, come back, and they’d still be glaring at each other across a snowy field. For some people, that’s unbearable. For me, if I’m in the right mood, the deliberate pace is part of the point. It lets the paranoia breathe and draws out every little fracture in the characters. Still, I won’t pretend I haven’t checked the time once or twice during that final hour. The emotional punch sneaks up on you. The film doesn’t treat Ford’s betrayal as some wild twist; it’s more about dread and inevitability, like watching a tragedy unravel in super slow-motion. And after the titular moment, it doesn’t speed to the credits but plods along, exploring the hollow aftermath. I respect that level of commitment to mood, even if it leaves you feeling a bit wrung out. Not everyone in the supporting cast lands, though. Some side characters feel like afterthoughts and the dialogue sometimes dips into self-importance. There are monologues that want badly to be profound, just teetering on the edge of pretentious. That and the relentless gloom can make sticking with it kind of a feat. All told, "The Assassination of Jesse James..." is more art film than gunslinger ride — poetry written in mud, obsession, and regret. It stumbles here and there under its own weight, but I think it’s a Western with actual emotional heft, unafraid to trade six-shooters for silences. I doubt everyone will love it, but I also doubt anyone will forget the vibe.

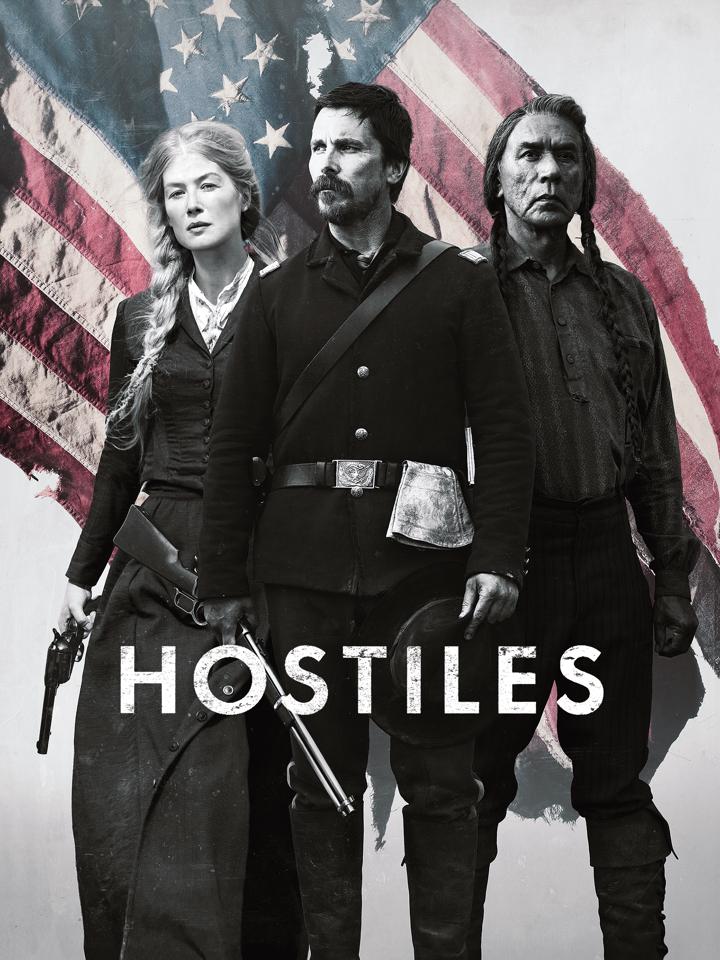

Hostiles is one of those modern Westerns that comes in quietly, loaded with more grit and heartache than gunplay. Set in 1892, it follows Captain Joseph Blocker (played by Christian Bale) as he reluctantly escorts a dying Cheyenne chief back to his ancestral land. From the very first scene, the film’s tone is heavy, almost haunting. Director Scott Cooper doesn’t rush through the setup, taking his time to let you sit with the violence and pain that shaped Blocker’s life. It’s not a fun watch, but it’s absorbing in a way I didn’t expect. What really stood out to me was just how somber everything feels. The landscape is breathtaking and brutal all at once: endless plains, dust-choked sunsets, and that sense of danger lurking just outside the frame. The cinematography leans into the harsh beauty of the American West, almost making the land itself a character in the story. There’s a lot of silence, too, not just in dialogue but in the way characters move and look at each other. It feels authentic, like the script trusts the audience to fill in the blanks with their own emotions. Christian Bale really pulls you in. His performance is layered and often wordless. Blocker is this man who’s done awful things in the name of duty, and you can see every bit of regret and self-loathing in Bale’s face. Equally impressive is Rosamund Pike, playing a widow whose family is killed in the movie’s brutal opening. There’s a scene early on when she’s shell-shocked and desperately clinging to a blanket, and Pike nails it without saying much. It’s painful to watch but so real. The film has a deliberately slow pace, and for the most part, it works. Cooper wants you to carry the weight of these characters, and honestly, by the halfway point, I started to feel it. Sometimes the pacing does teeter on being too slow, though, especially in the third act. There are stretches where it seems like not much is happening beyond riding and brooding. I get that it’s intentional, but there were moments I wished for a little more forward momentum. The themes here are heavy. Hostiles is about forgiveness, racism, and confronting the past, and it never sugarcoats anything. There’s a scene where Blocker and Chief Yellow Hawk (Wes Studi, dignified as always) have a conversation by a campfire. It’s tense and awkward because you know they’ve both seen and done terrible things. The movie gives these moments space and doesn’t rush to neat emotional resolutions. That honesty elevates it above most modern Westerns that try to paint things in black-and-white. Where the film stumbles a bit is in its supporting characters. There are a handful of sidekicks and soldiers, some played by recognizable faces like Jesse Plemons and Ben Foster, but they’re mostly there to underline a point or push the plot. I wanted more from them, especially Foster, who usually eats these roles up. Instead, most of them blend into the background, and their arcs wrap up quickly or unsatisfyingly. Tonally, Hostiles is pretty bleak. This isn’t a Western with wild shootouts or sunny days. It wallows in sorrow, and the violence, when it comes, is swift and jarring. Some viewers might check out because of how relentlessly grim it gets in parts. But for me, that’s actually what makes it work so well. There are real stakes here, and nothing feels sanitized or cheap. Ultimately, Hostiles left me with mixed feelings. It’s beautifully shot, impeccably acted, and honest to a fault about the darkness of its subject matter. But it’s hard to say I “enjoyed” it. It’s more like something you endure, and by the end, you’re left with a mixture of sadness and relief. If you want a Western that avoids clichés and makes you sit with the ugliness behind the mythology, this one is absolutely worth your time.

Dead Man is about as odd and hypnotic as Westerns get. Directed by Jim Jarmusch and starring a remarkably mournful Johnny Depp, it floats somewhere between a mythic fever dream and a sad folk ballad. The story? Depp is William Blake (no, not that one, though the confusion is deliberate), drifting west and destabilizing everyone he meets. The plot comes in fits and starts, more interested in mood than momentum. Visually, this movie is stunning. Shot in black-and-white by Robby Müller, every frame looks misty, grainy, and a little haunted, like some dusty old daguerreotype that got thrown into David Lynch’s bedside drawer. The landscapes are vast but oddly intimate, making you feel exposed and lost at the same time. There’s a lot of weird little moments too, like when characters have a conversation with their eyes instead of their mouths. The tone walks a tightrope between deadpan comedy and existential gloom. Nobody seems quite sure if they’re in a joke or in a funeral procession, and there are touches of surreal violence that kind of sneak up on you. Neil Young’s scorched-earth guitar score hums ominously under everything, like the plaintive pulse of some giant, unseen animal. It works and it shouldn’t, but it really, really does. Depp is quietly captivating, his William Blake a total outsider who seems to shrink and harden as the movie goes on. Gary Farmer gives a standout performance as Nobody - a Native American guide with sly humor and heart. The supporting cast is a weird who’s who of indie and character actors: Crispin Glover, Iggy Pop, Billy Bob Thornton, John Hurt. Only some of them get enough to do, though, and you’re left wanting a little more substance from the side characters. If you want a straight-shooting Western, you’ll be frustrated. The pacing is slow and often feels intentionally aimless. Sometimes scenes drag just to stew in their own strangeness. Not every conversation or detour goes anywhere. But that's kind of the point: Dead Man is all about creating atmosphere, not explaining everything or tying every thread together. If you’re patient and you dig movies that operate more on poetry than plot, Dead Man has a lot to chew on. If you prefer your Westerns with galloping horses, shootouts, and clearly drawn good guys versus bad guys, this will test your endurance. Either way, it’s one of those films that gets stuck in your teeth.

If you want a Western that actually feels brutal and unpredictable, The Proposition is a rare gem. Set in the scorched Australian outback, it’s got the bones of a classic Western but leans way grimier and more unforgiving. The basic setup is this: lawman Ray Winstone forces outlaw Guy Pearce to hunt down his even worse brother, or the family he’s left behind will pay the price. No comforting hero stuff here, just moral sludge and difficult choices. What immediately hits is how much the environment matters. Everything looks hostile. The landscapes are rugged and almost hostile, and you truly believe every character is desperate. The cinematography is both stunning and oppressive; the light’s all wrong and the flies never stop. It feels like everything is about to rot, and it keeps you on edge. The violence is jarring, but it never feels cartoonish or fun. Every gunshot has weight, and every injury lingers. There’s a fight in the dusty main street that’s messy in a way you almost never see in Westerns. The brutality actually means something - it’s painful, not cool. I appreciated that director John Hillcoat never gives you the satisfaction of a clean payoff. Acting-wise, Guy Pearce nails the haunted-outlaw thing, and Ray Winstone is fantastic as a “good guy” who barely seems above his prisoners. But the real standouts are Emily Watson as the lawman’s wife - she practically vibrates with tension - and Danny Huston, whose villain has a kind of philosophical weirdness that’s hard to look away from. The story’s pacing is kind of slow, so don’t go in expecting constant shootouts. It’s tense and quiet for long stretches, which can feel flat if you want pulpy fun. Sometimes that moodiness works, sometimes it makes you impatient - especially if you’re not already sold on bleak Westerns. Honestly, it’s not a Western you’ll walk away from feeling good. It’s intimate, nasty and morally murky, but it never feels phony for a second. If you like your Westerns dirty, loaded with atmosphere, and unafraid to get ugly about human nature, this is a must-watch. If you’re after an adventurous good time, you’re probably better off elsewhere.

So, have you ever heard of "The Homesman"? It’s a Western from 2014 directed by Tommy Lee Jones, who also stars alongside Hilary Swank. Set in the wind-blasted Nebraska territory, the story flips the usual Western formula - here, a tough, fiercely independent woman (Swank) takes center stage, tasked with transporting three mentally ill women back east. The premise is already pretty harrowing, and the movie definitely runs with that, giving a raw, more somber spin on the genre. What really stood out for me was Hilary Swank’s performance. She’s determined and vulnerable in equal measure; you honestly feel the weight of everything she’s carrying. Tommy Lee Jones plays a drifter pressed into helping her, and there’s a great, prickly dynamic between them that’s less about romance and more about mutual survival. The supporting cast is solid too (Meryl Streep pops up in a small, memorable role). Cinematically, the movie is gorgeous in a stark way. The endless landscapes feel both isolating and majestic, almost like another character. There’s a sense of authentic hardship - the cold, the mud - that grounds everything. The pacing is pretty deliberate, though, so if you’re looking for shootouts and bar brawls, this is definitely not that kind of Western. I will say, the bleakness sometimes risks being overwhelming. It doesn’t shy from how brutal pioneer life could be, and while that's refreshing, it also means the film can feel heavy and, at times, uneven in tone. There are flashes of dark humor (thanks Jones!) but mostly it’s a tough, sobering journey. It’s not perfect - some plot points wrap up a bit abruptly, and a few side characters don’t get quite the development they deserve. You would enjoy this if you like your Westerns with a bit of grit and a woman’s perspective, or if you’re just after something quieter and more reflective than the typical gunslinging fare. Definitely for fans of character-driven dramas and those who appreciate atmospheric filmmaking.